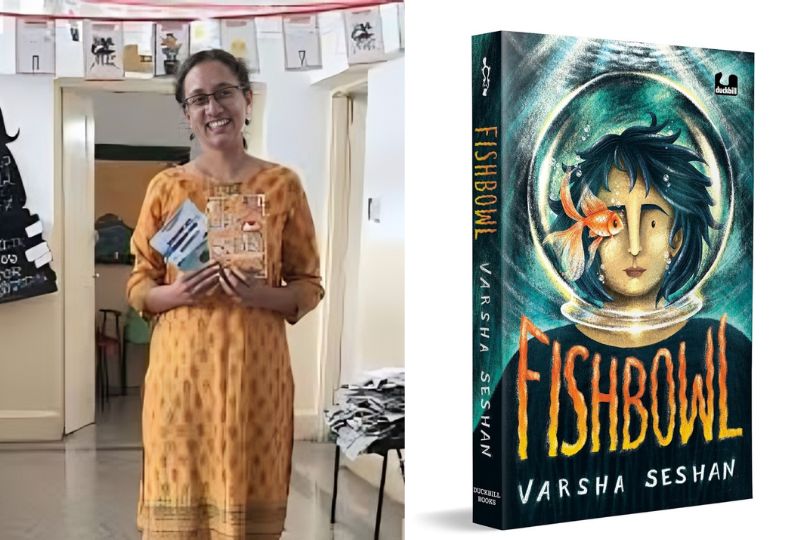

Interview with Varsha Seshan Author of “Fishbowl"

In Fishbowl, Varsha Seshan explores isolation, coping, and friendship, weaving complex emotions through Mahee's story of safety and vulnerability, perfect for young readers.on Oct 24, 2024

Varsha Seshan is a Pune-based children’s writer, with books published by Scholastic, Puffin, Duckbill, Young Zubaan, and more. She has been shortlisted for the AG-BLF Prize for Children’s Fiction, the Neev Book Award, the Singapore Book Award, and the Scholastic Asian Book Award. As someone who loves silence, rain and the possibility of magic, she is happier with plants than with people. She conducts online book clubs and writing programmes for ages seven to fourteen and is a classical dancer with over thirty years of training in Bharatanatyam. Find out more at www.varshaseshan.com

Frontlist: In Fishbowl, you've created a vivid metaphor for safety and isolation. What inspired you to choose the image of a fishbowl as the central motif, and how did it evolve during the writing process?

Varsha: This is a tough question to answer, though a lovely one!

Don’t all of us delude ourselves in some way or another? Especially as children, we make bargains — with God, with ourselves, with some sort of unnamed power …

So, for instance, we would say things like if such-and-such thing happens, I promise to do so-and-so.

We look for signs around us.

If I see two mynas, they’ll bring me joy. At some level, we don’t believe these things, but they continue to provide an illusion of control or safety.

It was this idea that inspired the fishbowl. Mahee’s fishbowl is isolating, but it keeps her safe. It is invisible, but she believes that it protects her in a way that is impossible to explain. It is, by its very nature, contradictory. It is something that is doomed to break, that must break, but that she holds on to for some semblance of control.

From what I can remember, this central motif was the crux of even my very first draft. I would say it is one of the very few things that didn’t change during the writing of the story.

Frontlist: Your characters, particularly Mahee, deal with difficult emotions like grief and trauma. How did you approach writing these intense themes while still maintaining a connection to a young audience?

Versha: Unnamed fear is a strange beast. During the pandemic, it was more palpable, but even when I was a child, way before any thought of a pandemic, I had a real fear of my loved ones dying. I clearly remember standing on the terrace and waiting when my mother came home late from work, constantly praying that she would be okay. In this way, anticipatory grief and crippling fear are written into our systems, or at least, it was written into mine. These are the emotions I explored and examined as I wrote Fishbowl. I explored them as the child I was as well as the adult I am.

Frontlist: Your story touches on some serious themes, but there are also moments of humor and warmth. How did you balance these emotions throughout the book?

Varsha: Nearly every book I write touches upon friendship in some way. Friendship, at its core, is about finding someone with whom you’re willing to be both vulnerable and silly. In Fishbowl, Aditi and Mahee epitomize that. Friendship is a safe space where they aren’t judged for doing something childish, and this is where humor and warmth are born.

Frontlist: Did you draw from any personal experiences or research while writing about the psychological aspects of the story while ensuring the concepts are not too overwhelming for the young audience?

Varsha: For me, some kind of personal experience is essential to the writing of an authentic story. Voices in my head, inner monologues about “real” reasons to seek help, tiny irrational bargains … I know I’ve had it all.

Research is crucial too, but for Fishbowl, many of the details are loosely (or not so loosely) based on friends’ experiences. When it comes to mental health and therapy, I’m much more trusting of firsthand accounts than the internet!

The first therapist in the story, for instance, is a direct retelling of a friend’s first encounter with therapy. The talking in metaphors is based on a groundbreaking moment for another friend.

In terms of ensuring that the concepts aren’t overwhelming for a young audience, I interact extensively with children and teens. I read what they write and I’m privy to their thought processes because of the writing programs I conduct. I will never underestimate the influence these young people have on what I write and the way I write it!

Frontlist: Was there a particular scene in Fishbowl that was particularly challenging to write, and how did you overcome that obstacle in the storytelling process?

Varsha: To be honest, the whole story was challenging to write! I wrote the book in prose first, and I rewrote it multiple times, changing major plot points each time. It was only when I wrote it in verse that I began to be happy with the shape it took.

No child going through trauma can think in beautiful, structured sentences. Verse was the only way for me to tell the story of Mahee’s fragmented, crumbling world.

Working with three narrative voices was challenging too, and it was my editor Sayoni Basu who helped with that, nudging me in different directions to make Ridhima’s voice and Aditi’s voice distinct.

Frontlist: For World Mental Health Day, how do you think your story, which touches on coping mechanisms and isolation, can contribute to discussions on mental health, particularly among younger audiences?

Varsha: While people are increasingly comfortable talking about therapy, actually seeking help is often, as Mahee puts it, an act of courage. It shouldn’t be, but it often feels like it. To validate this idea through what we read and watch is important.

Equally, it is important to be there for people who are going through a difficult time. But what does “being there” mean? What does it translate into? I think all of us struggle to answer these questions. It seems trite to say that you should not be judgmental or that you should check on people. Of course, these are important. But sometimes, it doesn’t feel like enough, and it leaves us feeling helpless. Talking about these things is important. As Aditi says in the book, I know it’s unfair,/But can you help me?/Can you tell me how you want me to be?

These conversations are important. How do you support someone who is having a panic attack? What is your role in helping someone else? And through it all, is your own struggle with mental health less important?

I think these are the conversations I hope to spark through this story, on World Mental Health Day, of course, but in regular day-to-day life too.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.