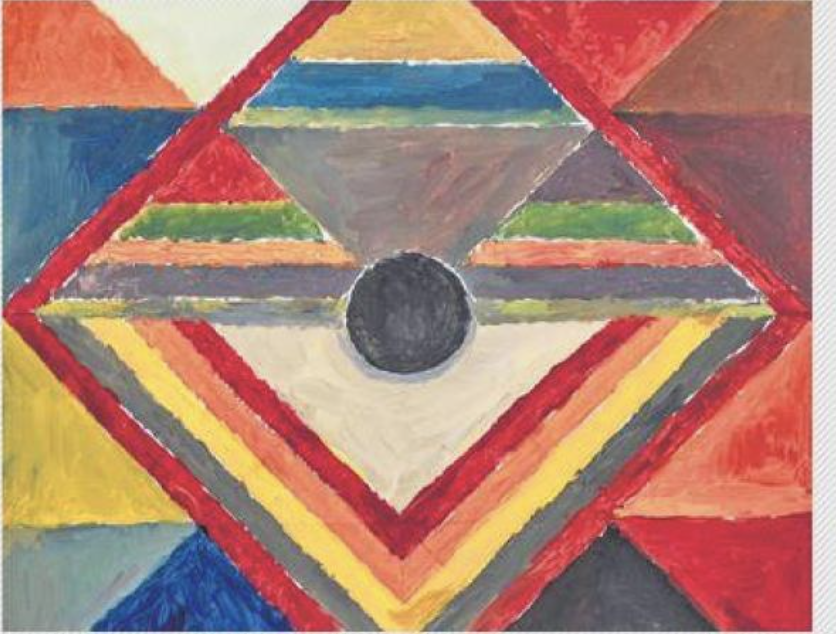

'Sayed Haider Raza is a biographer's dream'

'Sayed Haider Raza is a biographer's dream'on Apr 06, 2021

Raza passed away in 2016, and I was commissioned the book then. Many of his colleagues had also left the world, so getting the material on Raza’s life was difficult. But the artist was a great archiver. In a certain way, he is a biographer’s dream. He had kept his letters, notes, even his bills safely. All this compensated for his absence.

In the chapter titled Magical Flowers Were Humming, you have reproduced some letters Raza wrote to his wife Janine Mongillat, an artist herself. Could you talk about their relationship?

It was a love story in the true sense of the word. He met her almost as soon as he reached Paris, when he joined the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts. She was a fellow student, and they instantly took to each other. The remarkable thing about this relationship was they were very different from each other yet very similar. She was very down-to-earth in a French art society, and she was doing very contemporary works, whereas Raza was more philosophical and his works had to do with the domain of thought. They were, in many ways, together in their outlook towards the world, and their relationship was fulfilling.

Read more: https://www.frontlist.in/two-trend-setting-books-set-to-clear-the-air-on-indian-data/

They kept their practices very separate from each other. As Raza used to describe, they had their studios side-by-side, and they used to meet in the evening. When they got married, her parents were not very happy with the match. She had an upper class upbringing of a typical French girl where everything has to be just right, and being the only child, her parents had high expectations of her. And Raza, not only was he an Indian, he was also an artist and his future was uncertain. But Janine had found her upbringing in sort of gilded cage and wanted something which was wholesome, something more to do with real life. When she saw Raza, although his clothes were tattered, she was impressed because he had a paintbrush in his hand.

Janine was very sure that she wanted to marry Raza. And they did. After Raza got divorced from his first wife. It was an extraordinarily harmonious relationship. The many letters he wrote to her before marriage are full of passion and engulfed by her presence. When she died — her death preceded his by almost two decades — he was devastated. I don’t think he quite recovered from her loss. She was a real companion in every sense of the word.

The book mentions his grandfather as a part of the cultural milieu of Delhi. Could you elaborate on that?

Raza’s grandfather belonging to the well-known family of Delhi, was possibly associated with Bahadur Shah Zafar’s court. But he had to flee to Mandla during the Uprising of 1857. Raza’s coming back to the Capital in 2016 and activating the Raza Foundation to promote young artists and larger cultural ethos of the city, was in a way turning the wheel full circle.

How did diverse religions impact Raza?

Like his father, Syed Muhammad Razi, Raza was open to all religions. The artist was a Shia Muslim, but visited a church every day in France and thereafter proceeded to his to studio to work. Interestingly, he did various religious things, which Janine didn’t follow such as attending the Sunday Mass. He often used to say that without a spiritual energy, no work of art could take place.

Source: https://www.newindianexpress.com/

In the chapter titled Magical Flowers Were Humming, you have reproduced some letters Raza wrote to his wife Janine Mongillat, an artist herself. Could you talk about their relationship?

It was a love story in the true sense of the word. He met her almost as soon as he reached Paris, when he joined the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts. She was a fellow student, and they instantly took to each other. The remarkable thing about this relationship was they were very different from each other yet very similar. She was very down-to-earth in a French art society, and she was doing very contemporary works, whereas Raza was more philosophical and his works had to do with the domain of thought. They were, in many ways, together in their outlook towards the world, and their relationship was fulfilling.

Read more: https://www.frontlist.in/two-trend-setting-books-set-to-clear-the-air-on-indian-data/

They kept their practices very separate from each other. As Raza used to describe, they had their studios side-by-side, and they used to meet in the evening. When they got married, her parents were not very happy with the match. She had an upper class upbringing of a typical French girl where everything has to be just right, and being the only child, her parents had high expectations of her. And Raza, not only was he an Indian, he was also an artist and his future was uncertain. But Janine had found her upbringing in sort of gilded cage and wanted something which was wholesome, something more to do with real life. When she saw Raza, although his clothes were tattered, she was impressed because he had a paintbrush in his hand.

Janine was very sure that she wanted to marry Raza. And they did. After Raza got divorced from his first wife. It was an extraordinarily harmonious relationship. The many letters he wrote to her before marriage are full of passion and engulfed by her presence. When she died — her death preceded his by almost two decades — he was devastated. I don’t think he quite recovered from her loss. She was a real companion in every sense of the word.

The book mentions his grandfather as a part of the cultural milieu of Delhi. Could you elaborate on that?

Raza’s grandfather belonging to the well-known family of Delhi, was possibly associated with Bahadur Shah Zafar’s court. But he had to flee to Mandla during the Uprising of 1857. Raza’s coming back to the Capital in 2016 and activating the Raza Foundation to promote young artists and larger cultural ethos of the city, was in a way turning the wheel full circle.

How did diverse religions impact Raza?

Like his father, Syed Muhammad Razi, Raza was open to all religions. The artist was a Shia Muslim, but visited a church every day in France and thereafter proceeded to his to studio to work. Interestingly, he did various religious things, which Janine didn’t follow such as attending the Sunday Mass. He often used to say that without a spiritual energy, no work of art could take place.

Source: https://www.newindianexpress.com/

Author

Authors

Book

book news

Books

Frontlist

Frontlist Book

Frontlist Book News

Sayed Haider Raza

Yashodhara Dalmia

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.