We are living through a time when identity drives society, polity, war, advertising’: Jeet Thayil

We are living through a time when identity drives society, polity, war, advertising’: Jeet Thayilon May 28, 2021

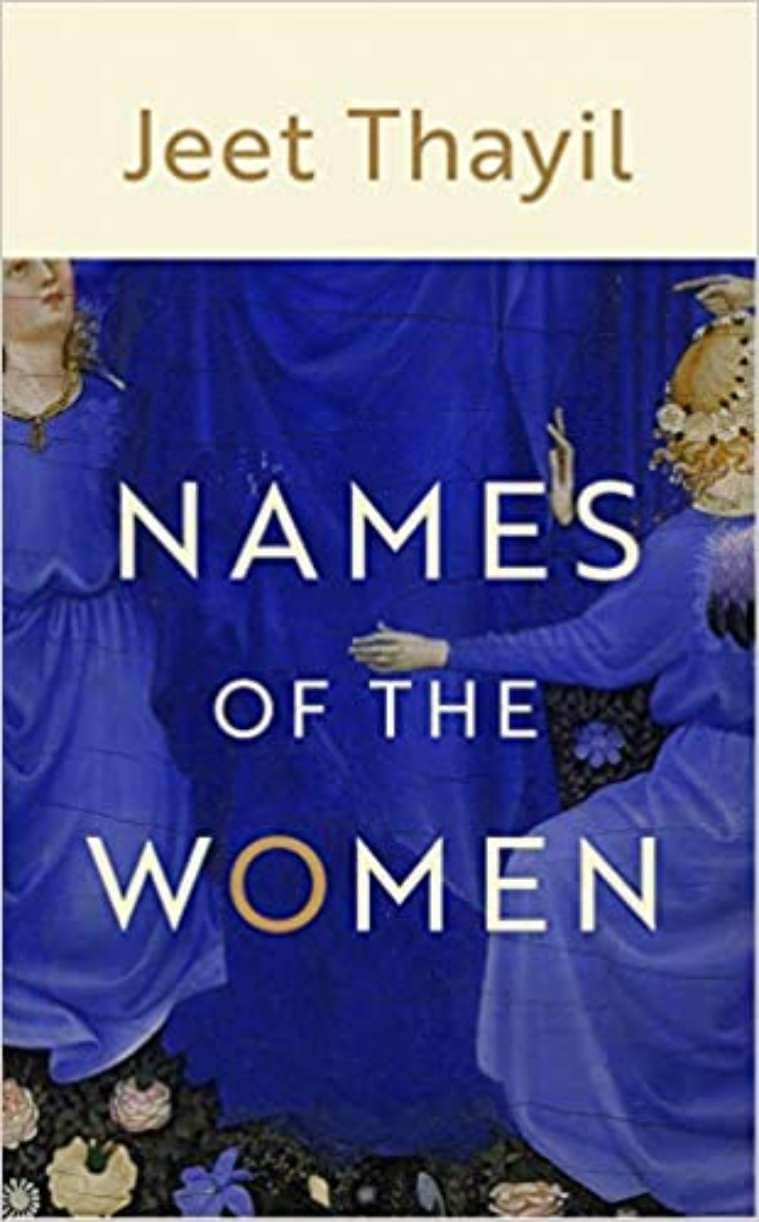

“Stories are all we have”. (Source: Amazon.In)

There has been some criticism of the fact that you do not acknowledge Jesus’s ‘Jewishness’ enough. How do you respond to that?

I don’t agree. His Jewishness is never in doubt. It’s just that I gave more prominence to the radical stance he embodied in relation to the rich, the corrupt, the idea of forgiveness, and the position of women, than the faith into which he was born and against which he rebelled.

The language in the novel has a distinctive Biblical influence. How easy or difficult was it to work with that register throughout the book?

It was the great pleasure of writing the book and I was astonished at how easily it came to me. I don’t know. It must say something about the voices in my head. They are loud and insistent, I’ll say that much, and sometimes they speak Aramaic.

Did the completion of the Bombay trilogy come with a sense of loss or freedom?

Absolutely a bit of both, I think. There was regret that it was over, combined with some kind of relief. I’d like to say I’m working with a clean slate now, but that’s never the case, is it? Your slate’s a palimpsest: you always find the scratches left by the years.

Have you been working on something new?

I’m finding it difficult to get any work done, to tell you the truth. I mean, considering the news we wake up to each day, literature seems futile. At the same time, stories are all we have. I don’t know. There’s no training for a moment like this.

The Shakti Bhatt award has been one of the few literary prizes that has kept itself open to change to accommodate the demands of the time. This year, the announcement of the prize money being contributed to COVID-19 relief work emphasised the need to rely on each other to see us through. At a time of such deep distress and inequality, what role do you envisage for literature?

We are living through the worst crisis India has experienced in its modern history, I don’t think literature has any kind of role. It seems like a ridiculous claim to make. Indians are asphyxiating in hospital beds, on floors, while waiting in rickshaws and cars. Rural areas, which make up more than half the country, have been hit the hardest because of the lack of the most basic healthcare. Wood is too expensive and so we throw the bodies of our loved ones into the Ganga. The latest calamity to hit us is the black fungus, which chokes your lungs and is extremely contagious. Meanwhile, our leader makes ringing speeches and practises his tear-jerking skills. It’s clear that we have to depend on each other. We thought this year’s Shakti Bhatt Prize was a way of doing that. It may be inadequate, but it’s something.

Source: https://indianexpress.com/

“Stories are all we have”. (Source: Amazon.In)

There has been some criticism of the fact that you do not acknowledge Jesus’s ‘Jewishness’ enough. How do you respond to that?

I don’t agree. His Jewishness is never in doubt. It’s just that I gave more prominence to the radical stance he embodied in relation to the rich, the corrupt, the idea of forgiveness, and the position of women, than the faith into which he was born and against which he rebelled.

The language in the novel has a distinctive Biblical influence. How easy or difficult was it to work with that register throughout the book?

It was the great pleasure of writing the book and I was astonished at how easily it came to me. I don’t know. It must say something about the voices in my head. They are loud and insistent, I’ll say that much, and sometimes they speak Aramaic.

Did the completion of the Bombay trilogy come with a sense of loss or freedom?

Absolutely a bit of both, I think. There was regret that it was over, combined with some kind of relief. I’d like to say I’m working with a clean slate now, but that’s never the case, is it? Your slate’s a palimpsest: you always find the scratches left by the years.

Have you been working on something new?

I’m finding it difficult to get any work done, to tell you the truth. I mean, considering the news we wake up to each day, literature seems futile. At the same time, stories are all we have. I don’t know. There’s no training for a moment like this.

The Shakti Bhatt award has been one of the few literary prizes that has kept itself open to change to accommodate the demands of the time. This year, the announcement of the prize money being contributed to COVID-19 relief work emphasised the need to rely on each other to see us through. At a time of such deep distress and inequality, what role do you envisage for literature?

We are living through the worst crisis India has experienced in its modern history, I don’t think literature has any kind of role. It seems like a ridiculous claim to make. Indians are asphyxiating in hospital beds, on floors, while waiting in rickshaws and cars. Rural areas, which make up more than half the country, have been hit the hardest because of the lack of the most basic healthcare. Wood is too expensive and so we throw the bodies of our loved ones into the Ganga. The latest calamity to hit us is the black fungus, which chokes your lungs and is extremely contagious. Meanwhile, our leader makes ringing speeches and practises his tear-jerking skills. It’s clear that we have to depend on each other. We thought this year’s Shakti Bhatt Prize was a way of doing that. It may be inadequate, but it’s something.

Source: https://indianexpress.com/

Author

Authors

Book

book news

Books

Frontlist

Frontlist Book

Frontlist Book News

Frontlist Books

Frontlist News

jeet thayil

jeet thayil book

jeet thayil interview

jeet thayil new book

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.