The Books That Made Me: 8 Writers on Their Literary Inspirations

The Books That Made Me: 8 Writers on Their Literary Inspirationson Apr 16, 2021

The New York Times Book Review presented a group of writers under 40 with a simple challenge: Name the writer or writers who have most influenced your work and explain how. While many of these authors were just beginning their careers, they later became some of the most widely read and respected artists of their generation — Ann Beattie, Denis Johnson, Gloria Naylor and Frederick Barthelme, to name only a few.

In 2005, the Book Review repeated the experiment, talking to Susan Choi, Jhumpa Lahiri, Colson Whitehead, Gary Shteyngart, Jonathan Safran Foer and others about their influences.

It felt only right, then, that as a part of our 125th anniversary celebration, we pose the same question to writers of our day.

Megha Majumdar sensed that if the English language ‘could travel to me from those seasides I had never seen, it could also undertake more intricate journeys where I lived.’

Many summers in Kolkata we endured load shedding, or power cuts. With no warning, the fan would slow, the TV would dim, and if it was nighttime, we would sprinkle cool tap water on the sheets and try to sleep.

Sometimes, though, by the light of the emergency lantern I would read books like Enid Blyton’s “The Famous Five,” where the five ate scones on seashores (on break from solving mysteries). That reality was so alien that I couldn’t fully imagine it: I imagined a scone was like an ice cream cone. I did sense that if the English language could travel to me from those seasides I had never seen, it could also undertake more intricate journeys where I lived.

More than any foundational writer, this was the key revelation that allowed me to begin writing in English — the language, foreign as it was in my Bengali family, could hold the life I had. The more I read — and I read everything I could find on my parents’ shelves, from a Reader’s Digest atlas to Peter Matthiessen’s classic “The Snow Leopard” to R. K. Narayan’s “Malgudi Days” to Hermann Hesse’s “The Prodigy” — the more I gained confidence in this wobbly insight. I felt it when we bought peanuts from a seller who sat on the footpath and sifted sand in a hot vessel, and when I visited a fly-besieged sweet shop with my grandfather.

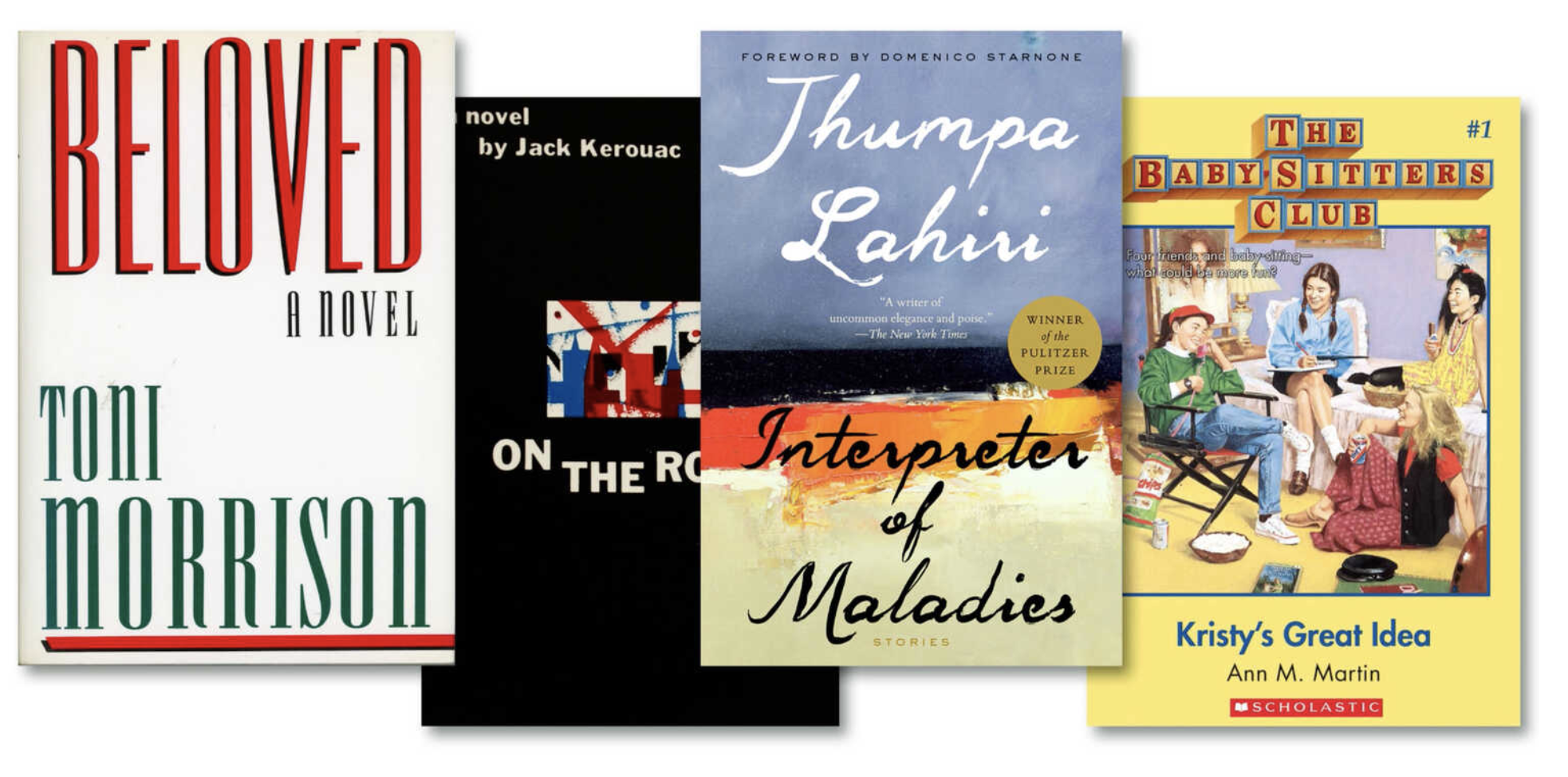

Then I read about load shedding in a story. A brilliant writer had turned this inconvenience into literary territory. It was Jhumpa Lahiri, and the book was “Interpreter of Maladies.” Reading it felt like being reintroduced to my own life.

Now I know that everything I read teaches me — about rhythm, emotional precision and variation, openings and endings, scene. Recently, I have loved books by Sanjena Sathian, Akil Kumarasamy, Yaa Gyasi, Elisa Gabbert and Angie Cruz.

Tommy Orange remembers that ‘Sylvia Plath’s “The Bell Jar” and John Kennedy Toole’s “A Confederacy of Dunces” made me pay to attention to what a novel could be.’

I was moving the whole fiction section from the back of the store to closer up front. This was a bookstore like they can’t exist anymore, two warehouses full of what was like 90 percent silverfish food. We weren’t very busy, so as I moved the books, I read them. I found Franz Kafka and Jorge Luis Borges — whose name I pronounced like the “g” in “gorges.” I loved what they were doing with language, with thinking. No one was telling me what to read then, I was out of school and doing it all on my own, so I read what I liked. Sylvia Plath’s “The Bell Jar” and John Kennedy Toole’s “A Confederacy of Dunces” made me pay attention to what a novel could be.

I read a lot in translation and learned to find the spines of publishers I liked, like New Directions and New York Review Books. Robert Walser really made me want to write. And soon after that, Clarice Lispector. What they were doing with consciousness and language, the playfulness and the power in their writing, really changed what I thought writing could do.

Alyssa Cole was only 7 when she ‘read “The Shining,” which ‘probably explains a lot about me, to be honest.’

I’m a multigenre writer, and this is the result of being a multigenre reader — picking up anything and everything I could get my hands on as a child. I’m focusing on childhood reads because, like many other writers, I think what we read as children — what makes us feel seen or, for marginalized readers, not seen — plants the seeds of the stories that grow in us over years and decades.

The first writer to show me that there were monsters in the world, and that they could be defeated (to paraphrase Chesterton) was Stephen King. (I read “The Shining” at age 7, which probably explains a lot about me, to be honest.) Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” imprinted upon me a different kind of horror, one that overwhelmed me because so much of it was rooted in the truth of America.

Romance, the genre of my heart, has three foundational texts in my personal canon: Jennifer Armstrong’s “Ann of the Wild Rose Inn,” a young-adult romance set during the Revolutionary War; Sandra Kitt’s “The Color of Love,” which was the first time I encountered a romance heroine who looked like me and, just as important, saw a romance writer who looked like me and realized maybe one day I could be one too; and Jennifer Crusie’s “Welcome to Temptation,” with its wit and banter and memorable characters.

I’d be remiss to leave out manga; I can’t imagine what my writing would be today — my sense of what’s possible — if I had never picked up Rumiko Takahashi’s “Ranma ½” and Johji Manabe’s “Caravan Kidd.” Probably one of the most pivotal books, now that I’m putting thought into this, is “The Armless Maiden: And Other Tales for Childhood’s Survivors,” edited by Terri Windling. This book (from my parents’ bookcase, like half of the books listed here) indulged my love of fairy tales, showed me the many different ways they could be reimagined, and is probably the latent inspiration for my love of writing shorter works and helping put together anthologies.

Emma Cline says that ‘Mating,’ by Norman Rush, is ‘a deeply pleasurable escape hatch,’ a novel ‘so big, in all senses, that your own life submits to it.’

The first-person voice is maybe my favorite part of the novel: The narrator is a Ph.D. student, neurotic and funny and brilliant, deeply self-conscious, deeply focused on romantic love as an absolutely central animating force while, at the same time, conflicted about the possibility of maintaining selfhood in a relationship. For these hundreds of pages, we’re swimming deep in her consciousness, following along with her riffs and asides, her minute shifts in thinking, her recounting of the sort of aimless but specific anecdote you pull from your past to illuminate yourself to a new partner, her X-ray vision reads of the people she meets. It’s as if a whole human life, a human consciousness, has been fully rendered in fiction, so that the narrator ceases to be a character at all.

Did I read somewhere or did I imagine that the narrator is a sort of loving ventriloquism of Norman Rush’s wife, Elsa Rush, even a kind of joint creation? I don’t want to look it up, to correct or confirm, because there’s something beautiful to me in thinking of the act of writing fiction as a way of dropping further into the world, a way of feeling out the contours of another person, another consciousness.

Yaa Gyasi read the Baby-Sitters Club series and the Anne of Green Gables books ‘over and over and over again, and, to my surprise, never tired of them.’

When I was in third and fourth grades, my family lived in the Cherry Grove apartment complex in Jackson, Tenn., above a woman whom I called Miss Mary. Most weekends, when the weather was warm, I would take a book out to the man-made lake in the middle of the grounds and read. Miss Mary must have seen me do this a hundred times or more, so when her daughter moved out, leaving behind several boxes of her childhood books, Miss Mary offered them to me.

I was a library kid, unused to the decadence of books you could write in or read at your leisure without the two-week clock winding down, so the gesture was unspeakably meaningful. Included in the boxes were the Sweet Valley High series, which I liked fine, the Baby-Sitters Club series, which I loved, and the Anne of Green Gables series, which, to borrow from Anne herself, became a kind of bosom friend.

I read them over and over and over again, and, to my surprise, never tired of them. In fact, each reading brought me a little more joy, helped me to see the characters a little more clearly. There was Diana, who was gentle and easy to love, and Gilbert who was smart, but frankly, a bit dull in his devotion to Anne, and there was Anne herself, defiant and assertive and loyal, a young woman who insisted her name be spelled with an “e” because she knew she deserved a little opulence in her life. I wonder how many young girls learned to claim space for themselves, value their intelligence and honor their desires because of L. M. Montgomery’s books.

While I was hardly thinking about craft lessons back when I reread the books to tatters, I can see their influence now simply in the fact that I chose this career at all, despite plenty of resistance. Anne taught me to insist on the “e.”

Yaa Gyasi’s most recent novel is “Transcendent Kingdom.”

Ottessa Moshfegh reveals, ‘“Invisible Man” was the book that made me want to be a writer. Just thinking about that book now makes my throat clench, my eyes water.’

My mother believed in excess when it came to literature — piles of books landed willy-nilly in every corner of the house where I grew up, curated from thrift stores and estate sales and curbsides. One day she brought home a box of books from someone emptying a library of 20th-century African-American literature. In it I found an autobiography by Dick Gregory. I think I was 9 at the time, and I picked the book because its title was a word that scared me. I’ve always been attracted to my own fear and anxiety, so this is where I began. All I had come to understand about the world thus far had been through the slim prism of my own existence, and yet I was already existentially despondent. It seemed that society was a farce, a satire of humanity. Nobody seemed to be telling the truth: school, television. I knew there was something fishy going on. Neither of my parents were born in America, I didn’t have a lineage that included any knowledge of the Black experience in the United States. Nobody told me. I needed literature.

Gregory was personal, political, engaging, an activist, a comedian and a completely unique voice on the page. In all the patronizing books for young adults I had been fed at school, here was the thrilling experience of someone telling his truth. There was no pretension, no fear.

The next book I read was “The Autobiography of Malcolm X.” Then I found Richard Wright. Then James Baldwin. Then the plays of Lorraine Hansberry. Then Langston Hughes. And then Ralph Ellison. “Invisible Man” was the book that made me want to be a writer. Just thinking about that book now makes my throat clench, my eyes water. It is a work of art — written with intimate beauty, pain, ecstasy, madness — and its power acts as a force of awakening upon the reader. It changed my vision. And so my standards as a writer were set high.

When I was a senior in college, I wrote two theses: one creative, one academic. My academic thesis was for a seminar about Black masculinity in American literature and film. I wrote about a Spike Lee film written by the playwright Suzan-Lori Parks called “Girl 6.” It is not at all strange to me that I have been most moved, most open to and interested in the works of African-American writers and filmmakers — in a white world that denied them, they told the truth. What else is there to do?

Gabriel Bump admits, ‘If this were a multimedia essay, I could include my misguided “East of Eden” tattoo. Thankfully, this is only words, so I can’t.’

I had brilliant older siblings and parents with bookcases to pillage, kind high school teachers willing to recommend non-assigned readings. Through them I would expand my interests beyond Sappy Masculine Standards.

Read more: https://www.frontlist.in/marwari-catalysts-ventures-unveils-edtech-batch-of-startups-for-its-edtech-accelerator-program-thrive/I found progressive African heroes on my sister’s shelves: Stephen Biko, Patrice Lumumba and Nelson Mandela. Toni Morrison through “Jazz” in Mr. Granzyk’s class. Jane Austen with Ms. Koenen. Mr. Branham welcomed me into his office during lunch, let me work through Sojourner Truth, James Baldwin and W.E.B. Du Bois.

In college — two years at the University of Missouri, two years at School of the Art Institute of Chicago, struggling to find my path, a drinking problem intensifying, vicious depression and anxiety swings — I became obsessed with wild plots, weirdness, powerhouse sentences and romance. I thank Adam Levin, my professor at SAIC, for directing my reading interests during those vulnerable years. Gogol, Saunders, Rachel B. Glaser, Ralph Ellison, Rebecca Curtis, Jeff Parker, Jesmyn Ward, Padgett Powell, Christian TeBordo, Barry Hannah, Harry Crews, Kaitlyn Greenidge and Denis Johnson. More than anyone, Johnson captured what I wanted from literature. His broad emotional register. His ability to see poetry and beauty everywhere. His generous style. “Jesus’ Son,” of course. Specifically, “Dundun,” a tiny story which I read daily while finishing my undergraduate thesis.

I found Johnson again in grad school, when I discovered stability and moderation. When I learned Johnson got sober, settled down and started to write his best stuff. Well, what better inspiration could I have received? Sure, I’ve slipped up a few times, found myself low. But that’s how life goes. That’s what great literature can teach us: Growth is complicated, often unpredictable and, if done with passion, always worthwhile.

Andrew Martin, who read a lot of Jack Kerouac as a teenager, says, ‘Kerouac’s persona as the sensitive chronicler of his harder, weirder friends’ exploits provided the template for what I imagined to be my role as a writer.’

As a teenager, the Beat writers — Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs and, especially, Jack Kerouac — seized my imagination completely, confirming my inner sense of grandiosity and alienation. Kerouac’s persona as the sensitive chronicler of his harder, weirder friends’ exploits (while still, of course, imbibing a heroic share of booze and heartbreak himself) provided the template for what I imagined to be my role as a writer for years to come. Only semiconsciously, I followed their ghosts to New York, and then to the mountain west and back, discovering subject matter for my fiction if not on the road, then at least, you know, near it. I’m grateful to the Beats for their bookishness and dogged enthusiasm for experience; undoing the influence of their destructive mythologizing and casual misogyny has been an ongoing literary project in itself.

I found deep kinship as a young man with a number of depressive, alcoholic male writers — Malcolm Lowry, Graham Greene, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Cheever, and Richard Yates — who also happened to be, thank God, brilliant stylists with much to teach beyond the heroic self-pity I was initially drawn to. After a few false starts, I made it through Samuel Beckett’s “Three Novels” in my 20s and it radically reshaped my idea of what fiction could be. Though I’ve never published anything particularly Beckettian, the garrulous freedom of his voice and his apocalyptic sense of humor are always in the back of my mind. I’m also often trying to draw on the powerful voices from the work of Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Philip Roth and James Baldwin, as remote as my own work is from theirs in style and substance.

The writers I’m most influenced by these days combine formal audacity with a streak of punk mischief. I’m thinking of Deborah Eisenberg, Renata Adler, Earl Sweatshirt, Robert Musil, Gary Indiana, Brenda Shaughnessy, Killer Mike, Ellen Willis, David Gates, Grace Paley and Garielle Lutz. The books I most want to write are “The Line of Beauty” by Alan Hollinghurst, “The Beginning of Spring” by Penelope Fitzgerald and “The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara.”

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.