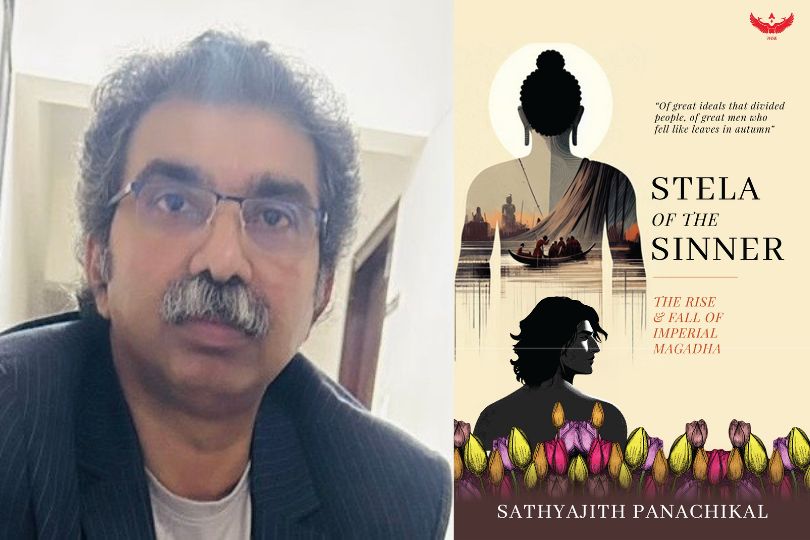

Interview with Sathyajith Panachikal, Author of “Stela of the Sinner”

A gripping historical epic set in ancient Magadha, Stela of the Sinner explores power, healing, and forgotten heroes through the eyes of royal physician Jivaka.on Jun 13, 2025

Frontlist: Your novel spans the rise and fall of Imperial Magadha during a transformative era in Indian history. What drew you to this particular period, and how did you balance historical accuracy with storytelling?

Sathyajith: While writing this novel, my brief to the writer in me was loud and clear- never violate the chronology of events. Even at the cost of the drama or suspense, an indispensable part of every fiction, I knew I must stick to the basics and play within the limits. That’s the problem with historical narrative: any writer who values etymological integrity cannot, for instance, use the word ‘assassination’ in a book that depicts an incident which happened before the Common Era, precisely because the term derived from the infamous murder cult of the Hashshashins of the 11th century AD.

It took me over seven years to complete this novel, the research into and the reconstruction of the bygone era consuming a good portion of the writing process. By and large, the fictional part of the novel constitutes only 20% of the story.

For those particular or curious about the historical accuracy, the book features a timeline of major events, although a fictional work is not supposed to substantiate its pretension of accuracy.

The story of ‘Stela of the Sinner’ unfolds during the Axial Age, a term coined by the famous German Philosopher Karl Jaspers. It was a great period of churn, both culturally and politically, with the present-day West Asia witnessing the advent of Zarathustra, India waking up to the Sermons of the Buddha and Mahaveera and China welcoming a new wave of philosophical discourses led by the likes of Confucius. It was also an era of incessant territorial expansions and intense battles, which constantly reshaped the borders of sovereign states. Post-Vedic India had a surprise strategist in Srenika Bimbisara, who not only proved equal to the task of bulwarking its defence against the formidable Achaemenid emperors Cyrus the Great and Darius I, but was an able administrator as well. The construction of the Great Wall of China was in progress in what was known as the Warring States period.

At this juncture, the Indian inventions of crucible steel and stirrups began changing the way wars were being fought. To put things in perspective, it had as much effect on ancient Warfare as the invention of the revolver did on modern ballistics.

With its six climatic seasons and fertile fields, India revelled in an abundance of food and comforts and even exported commodities such as jaggery, cotton and Indigo to lands far and near, not to speak of weapon-grade steel. Gandhara and Takshashila, once part of Greater India, fell under the yoke of the Persians, for which it remained the source of the largest revenue in terms of tribute and tax. Add to this the fact that it was also a time when India’s indigenous system of medicine, Ayurveda, was at its prime, with the introduction of manuals and pharmacopoeias made by stalwarts like Sushruta and Athreya revolutionising the medical science like never before.

Furthermore, I wish to highlight the fact, at the risk of being labelled jingoistic, that ancient India was an unbelievably prosperous, culturally vibrant, intellectually superior landscape which was too scientifically advanced for its time.

Ancient India and its people, collectively, served as a supercomputer that churned out invention after invention and provided solutions and discoveries.

It thought for the world.

Frontlist: The character of Jivaka—a royal physician born to a prostitute—is both marginalised and central. What made you choose him as the narrative anchor of this sweeping epic?

Sathyajith: As I have mentioned in the forward to the novel, it was my chance encounter with Jivaka, almost midway through the narrative, that prompted me to dig deeper to find out if this particular character had any significant locus standi on the vast canvas of the picture I was going to depict. To my surprise, he had a fascinating story, a voice of his own, and a stellar role to play, which more often were drowned out and dwarfed by the voices and acts of other dominant players of the theatre.

It will not be out of place here to mention that the editor of the book, Sandhya Sridhar, strongly objected to the use of the word ‘prostitute’ in the novel and suggested ‘courtesan’ instead. Euphemisms aside, prostitution was the first profession in the world, and its practitioners were, throughout history, always looked down upon by the world at large, their financial or political heft notwithstanding.

Jivaka, the narrator of the novel ‘Stela of the Sinner’, was not only the most revered physician of the period but was an active member of the Magadhan administrative machinery as well. His royal lineage, coupled with his impeccable medical background, made him an indispensable person not just in Magadha but also in hostile territories.

In Sangha and Jaina chronicles, Jivaka has been shown to have conducted a successful cranial surgery, an astonishing feat even by today’s standards. Although opening the skull and conducting an invasive neurosurgery was nothing new to the ancient world, it was for the first time that a specific individual was historically attested to have performed the complex procedure. While we might wonder how he performed brain surgery without anaesthesia, one should be equally inquisitive, if not suspicious, about the records that say Caesarean section predated Julius Caesar and that the ancient Egyptians performed complex dental implants and even brain surgery. More recently, it has come to light that Mayans and Incas of Mesoamerica had a near 90% success rate - a claim that needs to be taken with a pinch of salt- with trepanations (opening the skull surgically), centuries before the advent of modern medicine.

Amidst court intrigues and gory betrayals, Jivaka’s voice remained unusually sane, his integrity unwavering, and his mind stoical. He was a healer through and through. He cured the royals and commoners of their afflictions, both physical and mental. With the good of the empire at heart, he often risked his life to intervene in circumstances where the situation demanded it. The thrones changed hands, but the royal physician always lived another day to tell the tale, not because of his cunning or power but because he made himself unassailable through intellect, knowledge and skill.

Jivaka was a doctor, an administrator, a strategist and most importantly, a thinker, all rolled into one. He served Magadha during the reigns of three of its great monarchs. He provided succour to great men and women in their hours of need, all the while forgetting to live a life of his own.

What better narrator to chronicle the history of Magadha than a sagely figure who considered himself a loyal servant to King Bimbisara and was destined to treat none other than the Buddha?

Frontlist: Gautama Buddha plays a key role in the story. How did you approach writing a figure so revered and historically significant, especially in a fictional setting?

Sathyajith: That I was portraying the historical Buddha rather than the Grand Seer of one of the greatest spiritual movements in history gave me ample leeway for examining his life with a different lens. Buddha, the philosopher, does not need any fictitious image building to stand tall in any historical setting. Save for Diogenes, no thinker practised what he preached like Gautama Siddhartha did, perhaps. While chronicling his life, I could not have adopted any different approach than the one he would have taken to the mundane- that of detachment.

Frontlist: ‘None escaped the grudge and greed of mankind. Not even the Gods’ — this line is quite striking. Does it reflect your personal view of the cyclical nature of power and morality in history?

Sathyajith: ‘Gods’ here has been used as an allegory for great men. This is also an oblique reference to the epics of the Mahabharata, Ramayana and Iliad where human hubris blinded the mortals to such an extent that they ended up challenging celestial beings.

Devadutta’s betrayal of his more famous cousin Siddhartha is an all too familiar story of rivalry one might encounter in many a house of power before and after them. Similarly, the tale of a dynasty beset with a series of patricides or fratricides is nothing new if you are a discerning reader of history.

Greed, conceit and jealousy are a deadly combination and the perfect recipe for downfall. The graveyards of history are strewn with the headstones of people who succumbed to these temptations. Power - or the prospect thereof- intoxicates even the best of men into committing atrocities he would otherwise have desisted from.

In that sense, history is also an analysis of mankind’s continual failure to come to terms with their fallibility.

Frontlist: The novel combines politics, philosophy, medicine, and spiritual awakening. How did you manage to interweave such diverse themes without losing narrative cohesion?

Sathyajith: That the incidents in the novel occurred in a region which had long been a cultural melting pot helped structure a narrative that was laden with philosophical and spiritual overtones. And a protagonist, that too a doctor, who was always in the thick of things in terms of palace intrigues and healing, lent himself to be the common thread that connected politics and medicine.

The writer’s sole job was to lock each module of the episode into its proper slot, like assembling electronic equipment. Once everything falls in place, the story comes to life automatically. But the toughest part is creating those modules, each of which must contain expositions that further the plot without compromising mutual compatibility.

Frontlist: Many readers may not know about the Haryanka dynasty in detail. What challenges did you face in bringing this relatively obscure chapter of Indian history to life for a modern audience?

Sathyajith: The story of Bimbisara and Ajathasatru intrigued me the moment I read it, thanks to Amar Chitra Katha. While there is little dispute that Chandragupta Maurya qualifies as the greatest emperor India ever had, historians tend to ignore that Bimbisara was equally strong and was instrumental in safeguarding the country from such formidable foes as Cyrus the Great and Darius. Compare this to Chandragupta’s subjugation of Seleucus Nicator. Although Bimbisara did not have a showdown with Cyrus or Darius, he effectively thwarted their designs to invade India in the climacteric era. He and later his son Ajathasatru laid the foundations for Pataliputra, thereby restoring the glory of the erstwhile Magadhan Empire of the Vedic age. All that the Nandas, Mauryas and Guptas needed to do was to build on that momentum.

Bimbisara, who was the first ruler to have a standing army, the first to introduce tax collection, the only king destined to have extended patronage to the likes of Buddha and Mahaveera and nurtured an egalitarian society, in my view, called for more respect and admiration. But unlike Chandragupta or Ashoka, the hapless monarch and his reign had not left much archaeological evidence of note. Most of the chronicling on the said period comes from the Sangha and Jaina liturgy, which more often presented a conflicting narrative. I had to tread a middle path between these two major literary branches to reach a common ground.

And the abominable story of Ajathasatru, who seeks redemption from the sins of patricide, and who too would eventually face the same fate as his father, required a retelling. Then there was Udayabhadra, the last powerful ruler of the Haryanka dynasty, who completed the construction of the new capital of Magadha. However, historical records are few and far between when it comes to the question of what caused the delay in building the city at Pataliputra and who immediately succeeded Ajathasatru. For example, though King Darsaka of Magadha is one of the main characters in Bhasa’s Swapnavasavaduttam, the name of such a monarch is relatively absent in other historical works. There were contradictory accounts even of the way these rulers died and their dynasty perished. To make matters worse, two contemporaneous kings of almost identical names, illustrious royals in their own right, reigned over their respective contiguous territories in this era.

So did Jivaka, the protagonist and narrator of this chronicle who, despite being the most celebrated physician of his time, was conveniently sidelined by historians, relegating him to the obscure corners of the past. Other than ‘Jivaka Sutta’

and a few exaggerated Sramanic tales, the information available on the life of Jivaka was sketchy, to say the least. I had to juxtapose various anecdotes and incidents in which this personage appeared at different timelines to weave a composite tapestry depicting his temporal journey.

Frontlist: Was there a moment during writing where the story or a character surprised you, took a different turn than you expected? If so, how did that impact the overall narrative?

Sathyajith: Yes, there was one such haphazard turn in the narrative. For quite some time, my cerebrations about Ajathasatru’s immediate successor were leading me nowhere. The descriptions in the Vishnu Purana, Jaina and Pali literature seemed contradictory and unreliable. However, before long, from the dungeon of obscurity emerged a relatively unknown figure, Prince Darsaka, who not only usurped the crown but also turned out to be one of the most devious characters in the story. As I helplessly watched the novel’s plot running into doldrums, this character offered a much-needed tailwind with an unexpected manoeuvre. In hindsight, I feel this character had no other alternative but to do what he did to justify his brief existence in the annals of ancient history.

Frontlist: What do you hope readers take away from Stela of the Sinner—about history, power, or even healing through the character of Jivaka?

Sathyajith: History is the survivors’ account of the triumphs and the failures of humans, who are nothing but sailors aboard arcs of civilisations navigating the troubled waters of time. Whether one likes it or not, the world today is what it is because of what transpired in the past. While altering the past might remain as much a pipe-dream as the prospects of time travel are, we can at least analyse it, if not learn from it.

The pursuit of power was, is, and will be the prime mover of the wheel of historical narrative. It being a double-edged weapon, in the wrong hands, power becomes a scourge for the repression of lesser mortals. Since time immemorial, there has never been any difference in how humans behaved when they wielded power. They either flourished or perished with it.

As Hemingway said, we are all broken people. And our healing can happen in many different ways. It can be spiritual, mental or physical. Some people heal themselves through abandonment, others via reconciliation and renunciation. In Jivaka’s case, his chosen path to curing the wounds of humiliation and alienation was his unwavering dedication to his duty. But as he remarked, there are certain afflictions against which medicines prove ineffective- the ones a man inflicts on his conscience.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.