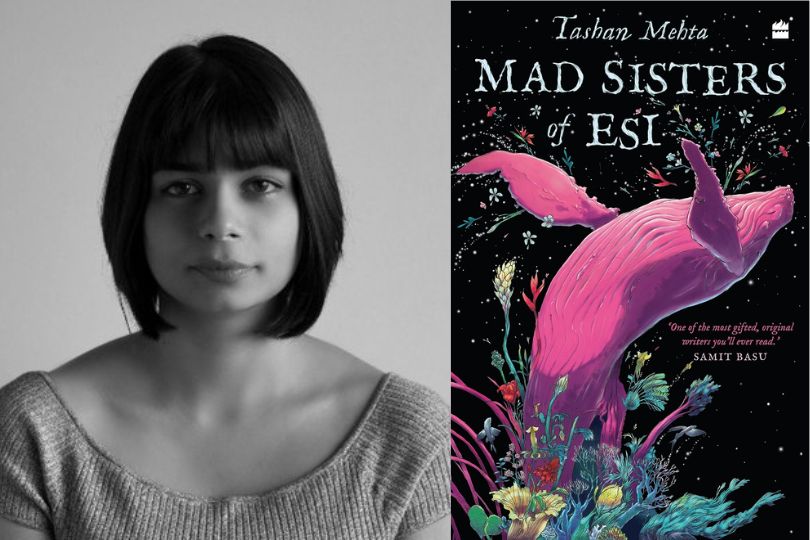

Interview with Tashan Mehta Author of “Mad Sisters of Esi”

Dive into an engaging interview with Tashan Mehta, the author of 'Mad Sisters of Esi,' revealing the creative journey behind this intriguing tale. Exclusive on Frontlist.on Dec 26, 2023

Tashan Mehta is the author of The Liar's Weave, which was shortlisted for the inaugural Prabha Khaitan Woman's Voice Award. Her short stories have featured in Magical Women, the Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction Volume 2 and PodCastle. She was fellow at the 2015 and 2021 Sangam House International Writers' Residency, India, and writer-in-residence at Anglia Ruskin University, UK.

Frontlist: The cosmic setting within the "Whale of Babel" is undeniably unique. What was the spark of inspiration behind this extraordinary locale?

Tashan Mehta: I've always been fascinated by humanity's desire to create something "god-like," as in the story of the Tower of Babel. If someone did manage to create something we considered "god-like," what would it look like? Would it be understandable to our minds? What would it be like to live in it?

The whale of Babel was born from that fascination. It went through many iterations: it started as a tower and then ended up as a cosmic whale; the inside of the whale kept changing form; and then once I settled on chambers within the whale, the chambers themselves went through numerous shapes. They began as the tall rooms you'd find in an abandoned palace, arranged around themes (I still love the Room of Treasure Chests and the Room of Dancing Cats), before evolving into galaxies with sentient doors, fabulist landscapes, and a wish-giving nature. The idea of "babel" always stayed at the heart of it, though—a chaos-creation that defies our understanding.

Frontlist: The title "Mad Sisters of Esi" is both mysterious and evocative. Can you unpack its significance in relation to the novel's central themes?

Tashan: I love how much everyone loves this title because I had to be convinced to use it. The first name for the book was Fairytales That Sing, which every beta reader vetoed. I then called it A Collection of Fishsilver Curiosities, at which point my sister and my best friend staged an intervention and strangled my protests of "But isn't 'fishsilver' the most beautiful word? It's like fish scales glinting in the light!" They assured me that no one cared.

So my book was once again in need of a name, and I was told it had to be obvious: something that kept the novel's central theme clear among the chaos. At that point, "Mad Sisters of Esi" was the name of one of the sections and became the most obvious candidate. The book is, in essence, about two sisters from the island of Esi who encounter the concept of madness (as unusually defined in this alternate reality) to sprawl a narrative much larger than themselves.

Once HarperCollins acquired the book and I was safe from both my sister and best friend, I tried to change the name again. No one would know how to pronounce or spell "Esi," I decided (largely because I'd made up the word), and it would hurt the book's chances of selling. It would be best to call it "The Mad Sisters." Once again, I was talked out of it, this time by my editor. She assured me readers would cope.

And indeed, they have. I'm glad the title stuck: I now can't imagine the book with any other name.

Frontlist: Your portrayal of 'madness' is evocative, painted not as a detachment from reality but as the very essence that creates it. Can you talk about the genesis of this profound redefinition?

Tashan: What a lovely question. I think this book is my attempt to find wildness and hold it close. I did a small artifact/book for the Barbican that had these lines:

but that's what you look for

for the magic of something that can't be broken down

into parts or methods

for the bit in art and life that lives

outside of understanding

The phrase "outside of understanding" really hit me. I wanted to write a novel that explored what that looked like, and that remade me in the process of that exploration—that pushed me out of old narratives and a stale imagination.

I chose "madness" as a name for it because it implies being outside the bounds of reality, and I wanted to convey that largess—of stepping out of logic and what we usually see as "real". It's both beautiful and terrifying, isn't it? I often say that the synonym for "madness" in this novel is "wildness," but it's also the "sublime": that feeling of awe and terror you get when you stare at the vast ocean and cannot see land when you gaze at a galaxy through a telescope or watch a wave climb to the height of a skyscraper. It's an acknowledgment of your smallness.

But terrifying as that is, it isn't disempowering—it cannot be. It's simply seeing clearly, seeing without the lens that keeps us "safe," seeing the brightness and bigness of the universe in all its wonder and if you can share in that wonder, surrender to it instead of fighting to control it, it's inherently empowering. It's just another, truer way of looking, and I wanted to create a world in which that had potency.

Frontlist: Fate seems to interweave the destinies of your characters, leading to dramatic intersections and conflicts. How do you view the interplay of destiny, free will, and serendipity in your narrative?

Tashan: It's so interesting that you picked up on fate in this novel, because I think it shies away from it: everything in Mad Sisters of Esi is the consequence of each character's actions and predispositions, often played out across galaxies and generations.

I read once that the trauma we experience finds its way into our DNA, and through there, it is passed on from generation to generation. We can find ourselves reacting to a certain incident in a particular way because of what our grandmother experienced. That similar reaction that mirroring might seem uncanny—it may seem like fate or serendipity—but it is logical, played out along channels we don't often look at (or know are there).

Everything seemingly mysterious in Mad Sisters of Esi works in the same way, even the magic. It's been seeded in the past, and now we're staring at the fruits of the present.

Frontlist: The intertwined tales of Laleh & Myung and Magali & Wisa are riveting. What fueled the creation of these captivating pairs, and why present their tales in tandem?

Tashan: I've been thinking about how to answer this without giving any spoilers, and I'm not sure I can. I will say, however, that two of the themes I wanted to explore in this book were belonging and identity. I was curious about how a person forms. Is it in isolation, some essential kernel to their nature, or is it in tandem with others through the reflections they provide? Both sets of sisters—Laleh and Myung and Magali and Wisa—allowed me to answer these questions and to look at their echoes across time. Both tales were presented in tandem because they were formed in tandem: they are echoes of each other, or as one reader called them, refractions.

Frontlist: Your storytelling, described by some as mirroring various arcs in the style of a "charcoal sketch," stands out. Why did you gravitate towards this specific narrative approach?

Tashan: I wish I had an answer for this one, but I did twenty-four drafts of Mad Sisters of Esi and five versions—which means any elegance in the structure or the nature of the narrative is best observed by a reader smarter than me. To me, Mad Sisters of Esi was endless digging—upending mounds and mounds of words to try and find the right ones, said in the right order. The final structure was the best shape I could wrestle the chaos into while keeping its unpredictability. It felt less like the elegance and lightness of a charcoal sketch and more like wrestling snakes into a workable rangoli pattern.

Frontlist: Magic unfurls mysteriously in your tale, with no exhaustive system explaining its intricacies. What motivated this decision?

Tashan: Oh, I think there is so much in our world that we don't understand. It felt silly to pretend that magic in an alternate universe would have its rules known, categorized, and understood by everyone in that universe. I was very clear I wanted to write a novel with our smallness squarely in mind—with the limits of our reality and consciousness and love and self—and logical systems tend to suggest an omniscience we humans don't really have. I wrote a fun little pamphlet about how time works in the whale of Babel for myself, but there was no reason to share it with readers—it didn't impact the story in any dramatic way, much like gravity isn't something I spend a lot of time thinking about.

I feel like our desire for exhaustive systems comes from our desire for control, to feel like we are rooted in the world around us and can make sense of it. But the truth is, we can't—not even with our world. Who knows why quantum physics behaves the way it does? They're saying now that particles can be entangled across time. Other particles change their behavior when you look at them. There is just so much we don't understand. We're small—we keep pushing the frontiers of our knowledge, but we certainly can't see as widely as we believe. We get through our daily lives by not thinking about how the chair we're sitting on is a collection of vibrating molecules held together (possibly?) by antimatter. I wanted the characters in my novel to look. I wanted readers to feel what it is like to swim in the vastness of our minuteness. That meant throwing them into the chaos and asking them to embrace it.

Frontlist: Lastly, readers often mention a feeling of being plunged into the story's epicenter sans a roadmap. Was this a deliberate choice, and what ambiance or experience were you striving to offer readers through this method?

Tashan: Honestly, it was the only opening that worked. I've tried every other opening for this book—opening with Ojda, starting with Esi—but each of them lost the reader. Believe it or not, the Whale of Babel was the least confusing start.

For me, the opening achieves two things. First, as you pointed out, readers feel dropped into the middle of the story, and that's a good thing, because it builds anticipation for the heart of the story—Esi—and helps them empathize with Myung (she is also lost, and it's easy to feel sympathy for someone like that when you're lost too).

But the second thing is far more critical: it anchors the reader, not in time or place, but in a person. In essence, Myung is on the same journey as the reader: she's seeking the same story, and she has the same questions. Anchoring them in her quest keeps them safe through all the acrobatics that the novel does with time and space. The novel has to open with the whale of Babel because that's where Myung's story starts.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.