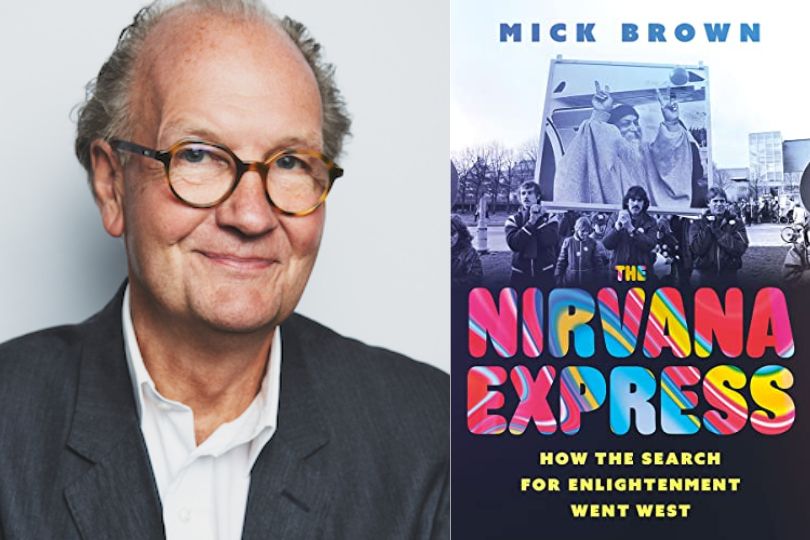

Interview with Mick Brown Author of “The Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment Went West"

Discover Mick Brown's author interview on 'The Nirvana Express' exclusively on Frontlist. Delve into the Western fascination with Indian spirituality, tracing the history of gurus and seekers. Uncover a captivating journey in this enlightening conversation.on Dec 15, 2023

Mick Brown is a journalist for the Daily Telegraph. His books include The Spiritual Tourist: A Personal Odyssey Through the Outer Reaches of Belief; The Dance of 17 Lives: The Incredible True Story of Tibet’s 17th Karmapa; and Tearing Down The Wall of Sound: The Rise and Fall of Phil Spector.

Frontlist: What motivated you to write 'The Nirvana Express' and delve into the West's fascination with Indian spirituality?

Mick Brown: It's a subject I've long been fascinated by. As a teenager in the 60s, going into the 70s, I was intrigued by the writings of Alan Watts on Zen Buddhism, Ram Dass's book Be Here Now, and Herman Hesse's Siddhartha; the Beatles taking up the Maharishi Mahesh, 'Mahavishnu' John McLaughlin and Carlos Santana becoming devotees of Sri Chinmoy…all of these things were very much part of the cultural terrain in the West at the time - not to mention the thousands of young people on the hippie trail heading to India in search of enlightenment.

In 1998, I published a book, The Spiritual Tourist, exploring different facets of this interest, visiting the Sai Baba ashram in Puttaparthi, the Aurobindo ashram and Auroville in Pondicherry, and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in north and south India. In 2004, I wrote The Dance of 17 Lives, telling the story of Tibet's 17th Karmapa and the schism that had arisen within the Kagyu school following his recognition - a study of the relationship between magic and politics in the reincarnations of Tibetan lamas.

Most people in the West think the relationship with Indian spirituality began with the Beatles. Writing this book, I was interested in tracing the history back to the time of the first Indian swami to come to the West in the mid-19th century, Swami Vivekananda, and then following this path through the stories of a fascinating variety of individuals - gurus, seekers, saints, and charlatans, including Edwin Arnold, Annie Besant, Meher Baba, Paul Brunton, Ramana Maharshi - up to the LSD guru Timothy Leary and Rajneesh.

Frontlist: Do you possess a personal connection or a particular affinity with Indian spirituality or any of the specific figures mentioned in your book? How has the process of writing 'The Nirvana Express' influenced or changed your personal perspective on the topic of Indian spirituality?

Mick: I think writing my two previous books had disabused me of any starry-eyed notion of the immaculate perfection of guru figures - what you might call Shangri La syndrome. And in my journalism, I've written investigations into the scandals surrounding Sai Baba and the Tibetan-Buddhist lama Sogyal Rinpoche.

I think at times, and with certain individuals, holding an overly romantic view - along with a lack of understanding - of Indian spirituality had led to Westerners being very disillusioned with what they found.

In the book, I write about Guru Maharaj Ji, who came to Britain and the US in the early 70s when he was just 15, gathered a large following and was hailed as the new messiah - a claim that was somewhat undermined when he married an air-hostess who was one of his followers and bought an estate in Malibu. That's an extraordinary story.

That said, of the gurus I write about in the book, I greatly admire Vivekananda, his ecumenical approach, and Krishnamurti, his belief that one must find one's own way to the truth.

More generally, I've traveled in India a lot, and I'm always deeply moved by the everyday expressions of faith - the street-corner shrines in Kolkata and other cities, the crowds milling through the Meenakshi temple in Madurai. Those rituals and beliefs are in the very grain of India and hard for a Westerner to fully comprehend, but even as an outsider one can share in the sense of humanity's connection to something ineffable and transcendent.

Frontlist: In your book, you discussed Rajneesh (Osho) and highlighted his status as one of the most controversial gurus of his time. What, in your view, made him so controversial? Do you believe the judgments and perceptions surrounding him were accurate?

Mick: The judgment and perceptions are so varied it's hard to say whether they're accurate. Rajneesh was a very interesting thinker in many ways. He saw it as his role to shake people out of their complacency, to challenge conventional mores and shibboleths, and to free the mind and the body, as it were. He was an iconoclast. But I think he lost control of himself and the movement he started. He got derailed by the adulation of his followers - worship is a powerful and dangerous narcotic - and the power struggles of those around him. The complete collapse of the Oregon ashram is the most telling illustration of who he became and the failure of his ambitions. Was he a genius or a charlatan? I think the answer is probably a bit of both.

Frontlist: In your opinion, is the influence of Indian spirituality still evident in contemporary society today?

Mick: In the West, less overtly so. The Guru Maharaj Ji ashrams of the 70s have all gone. The Rajneesh groups are fewer. The number of Westerners who flocked to India in the 60s, 70s, and 80s has dwindled. But I think the legacy of that 200-year-old Western fascination has been enormous.

In 1897 an Indian yogi named Bava Lachman Dass demonstrated yoga positions at the Westminster Aquarium exhibition centre, which The Strand, a popular periodical of the day, described as 'repulsive'. That was not an atypical view of many who had no understanding of Indian culture and beliefs. Today, yoga is one of the most popular health and leisure activities in the West, taught everywhere from health spas to parish halls - albeit in most cases a long way from its roots as a spiritual practice.

Once regarded as something strange and exotic, meditation is also practiced everywhere, 'secularised' and called 'mindfulness.' So, I think a growing understanding and appreciation of Indian spirituality has considerably enriched the lives of millions. It certainly has enriched mine.

Frontlist: What is your perspective on the potential for individuals to attain nirvana by following the teachings and paths of the gurus mentioned in your book?

Mick: I honestly don't think that's for me to say. I'm the last person to give anyone advice on attaining nirvana or suggesting who might best lead them there. For myself, I've always greatly admired the Dalai Lama and in particular his words that 'my religion is kindness'. As we know, simply being kind is not always easy, but I think it's a good place to start.

So my book is certainly not intended as a guidebook to gurus, good or or bad. My hope is that readers find it interesting and illuminating - I hesitate to use the word enlightening! - but above all, entertaining.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.