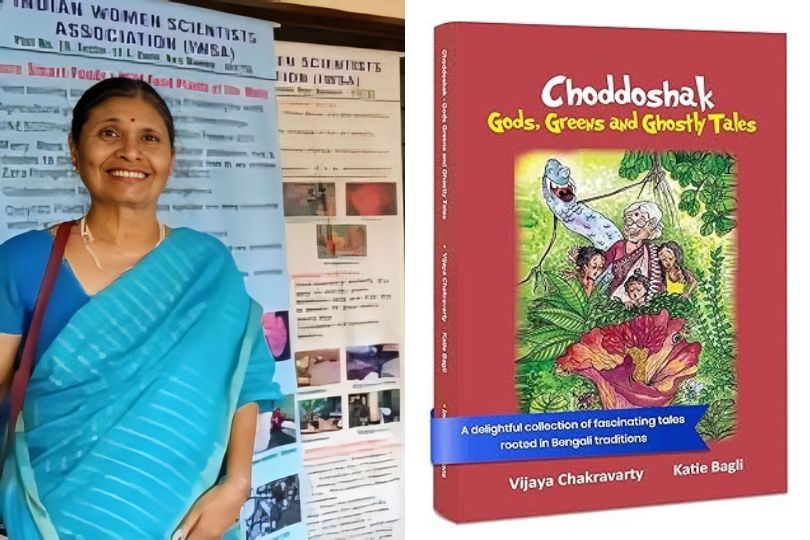

Interview with Vijaya Chakravarty Author Of Choddoshak : Gods, Greens and Ghostly Tales

Vijaya Chakravarty's Choddoshak explores traditional Indian folklore, conservation, and heritage through stories of plants, cultural practices, and family bonds.on Nov 04, 2024

About the Author

Vijaya Chakravarty, is an Author and a Landscape Designer at Harit Landscapes.

Vijaya Chakravarty started her career as a lecturer at St. Xavier's College. She combines writing with teaching, research, and practice. Vijaya tries to promote traditional conservation practices through her books.

Frontlist: Choddoshak is steeped in Bengali tradition. Can you share what inspired you to incorporate these cultural elements into your storytelling?

Vijaya: In 2018, I was working on Ethnobotany with a focus on plants used in Indian festivals. Each step of my research revealed bags full of tales, especially when I discovered multi-vegetable curries across the Indian subcontinent. I consulted with Dr. Saraswati Unnithan, Dr. Susan Eapen, Dr. Srirupa Mukherjee, Ms. Manik Gade, and Dr. Dhanashree Patil about different dishes prepared during festivals and specific seasons, both as offerings to deities and to boost immunity. Many plants and pollinators are well-documented in Indian scriptures and folklore.

This research led to several articles, lectures, and research papers. In 2022, some of these multi-vegetable recipes were included in my book Wild Forgotten Foods, published by Vigyan Prasar in collaboration with the Indian Women Scientists' Association. Then, in 2023, I co-authored Choddoshak: Gods Greens and Ghostly Tales with Ms. Katie Bagli, a well-known children’s author. The book won the Enlitt Book award for the best children’s book on conservation.

The 14 vegetables featured in Choddoshak are disappearing from the market and our plates. Many of these greens have roots in our culinary history and are mentioned in our epics, scriptures, folk tales, rhymes, and sacred songs (bhajans). They’re nutrient-dense, medicinal, and climate-smart. Most of them grow as edible weeds in rice fields, especially in Bengal, where ecologist Dr. Vandana Shiva says there are over 80 species of edible weeds. Traditionally, women, the custodians of family nutrition, gathered these greens from the wild.

With the Green Revolution and increased pesticide use, many of these weeds were lost. I’ve worked extensively on nutrition and the issue of “hidden hunger” or micronutrient deficiency in children. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals focus on zero hunger and nutrition, which is now seen as a key to achieving all 17 SDGs. I found that children, their parents, and seniors were fascinated by these ancient curries and ingredients, which were slowly being erased from memory. I received invitations from schools, colleges, book clubs, conferences, and senior citizen clubs for storytelling, nature trails, and talks on nutrition and traditional foods. It was a roller-coaster ride!

Frontlist: The tradition of cooking a meal of fourteen greens on Bhoot Chaturdashi is unique. Can you elaborate on the significance of this practice and its impact?

Vijaya: Indian food is rooted in vegetarianism, diversity, seasonal ingredients, spices, and Ayurvedic principles. Food is amrit, a prasad—an offering to God—and a charity for all beings, including animals and even souls from the netherworld. It’s integral to rituals and, in its essence, should leave us feeling “tripta”—a state of satiety with a lingering pleasant taste. That’s the spirit I tried to capture in the book.

Multi-vegetable cuisine using uncommon ingredients is seen in special dishes like Choddoshak in Bengal, Rishi chi bhaji in Maharashtra, Pathila Thoran in Kerala, and Khatkhate in Goa. Despite the fact that there are over 30,000 edible plants globally, we consume only about a dozen regularly. The world is abundant with edible plants to discover, and our book is a call for food technologists, nutritionists, and researchers to diversify our diets. Eating a wider variety of plants can promote food security, nutrition, and biodiversity.

In the past, grandparents would take children to forests to gather edible leaves, tubers, fruits, and flowers, teaching them their culinary and medicinal values. Knowledge of botany, cuisine, culture, and medicine was passed down orally, ensuring continuity of traditions.

Frontlist: How do you view the role of storytelling in passing down knowledge and traditions from one generation to the next? How does this theme manifest in Dida’s interactions with her grandchildren?

Vijaya: Dr. Jane Goodall, the legendary conservationist, believes that storytelling can change attitudes, behaviors, and inspire action. Her work has greatly influenced me. Through my talks and books on traditional Indian conservation practices, I hope to revive food diversity and encourage experimentation with traditional diets. Storytelling preserved history, knowledge, and wisdom for thousands of years. Oral traditions fostered community bonding and created a unique identity. In contrast, younger nations face identity crises because they lack these rooted traditions.

Dida, the grandmother in Choddoshak, uses storytelling to create a bond with her grandchildren and gently teach them culture and values. She isn’t involved in their daily routines but connects with them during vacations when they visit, immersing them in outdoor life surrounded by greenery, birds, and butterflies. Nowadays, kids spend over 90% of their time indoors, leading to nature-deficit disorders. Through Dida, they experience the joy of nature, learning about traditions, values, and wholesome eating.

Frontlist: What was your writing process like for this book? Did you face any particular challenges in blending traditional recipes and ghost stories into a cohesive narrative? How did you overcome those challenges?

Vijaya: The book is set in Bengal, near the Himalayan foothills, where human-elephant conflicts are common. To engage children with nature and food, we focused on Choddoshak, a dish traditionally prepared on Bhoot Chaturdashi, or Naraka Chaturdashi in other parts of India. On this day, Bengalis believe Goddess Durga visits Earth, accompanied by ancestors and ghosts. Homes are lit with lamps to guide ancestral spirits, and this led to the idea of incorporating ghostly characters into the book.

My three-year-old grandson loves animals and supernatural beings, so we researched Bengali ghost lore and found endearing spirits with human qualities. We created characters like Bacha Bhoot (Child Ghost) dressed in a flashy shirt reminiscent of Amitabh Bachchan’s iconic style, Machar Bhoot (Fish-loving Ghost), and Sonar Bhoot (Golden Lady Ghost). Some greens, like Bathua and Giloy, are associated with historic figures in Indian mythology, creating connections that children can understand and enjoy.

Frontlist: How do you envision readers, especially children, engaging with the book? What kinds of discussions or activities do you hope it inspires within families?

Vijaya: I hope that children and parents will absorb the science of growing, cooking, and eating. The COVID pandemic forced people into isolation, but a positive outcome was that millions took up gardening for the first time. Exchanging seeds, saplings, and recipes became a favorite pastime.

Choddoshak has sparked greater interest in local and seasonal foods. Katie and I have received requests for storytelling sessions, and we’ve been visiting schools and NGOs to share stories that connect children to traditions and bring families together. The role of ethnobotany in research is growing rapidly, and there’s renewed interest in traditional foods, natural food colors, plant-based fragrances, and more.

My multidisciplinary background has opened up new avenues, and I meet people from all walks of life—academics, activists, chefs, educators, and researchers. Nature-based learning has emerged as a key to a better world. With that in mind, I started a video podcast, Bifocal Naturalist, to connect ordinary people, animals, and plants with policymakers. This platform is a way for us to learn from each other and make a meaningful difference.

Frontlist: Do you have a favorite story from Choddoshak that holds special meaning for you? If yes, why does it resonate with you personally?

Vijaya: My favorite story is The Weed with Fish-like Eyes, which my mother told us as children to encourage us to eat greens. She called it Ponnaganti (Alternanthera sessilis or shalinche in Bengali). In the story, a poor, bedridden old woman is fed this green by her widowed daughter-in-law. She eats it three times a day until, miraculously, she rises, her face glowing, eyes bright. I loved the story, and it made me want to eat Ponnaganti, imagining it would give me radiant skin.

When I moved to Maharashtra, my mother didn’t know the Marathi name for Ponnaganti, so it remained a mystery. Fifty years later, at the Heartfulness Meditation Centre, I saw the leafy vegetable growing and was thrilled to learn it was Ponnaganti. I immediately planted it in Mumbai and shared it with friends and plant lovers.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.