Frontlist | Five writers name books they enjoyed reading in 2020...

Frontlist | Five writers name books they enjoyed reading in 2020...on Feb 03, 2021

What did ‘writers’ read this year and what are the books they would recommend? Ashlin Mathew caught up with Annie Zaidi, Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, Krupa Ge, Nisha Susan and Omair Ahmed

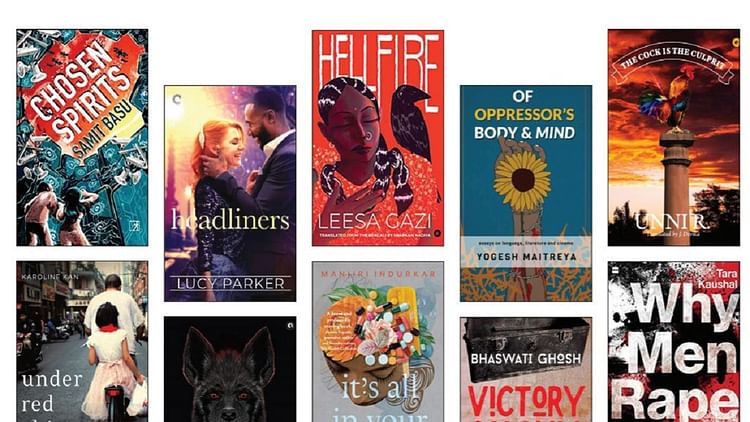

What did ‘writers’ read this year and what are the books they would recommend? Ashlin Mathew caught up with some of the Indian writers in English to find out. They have recommended 18 books in all, 13 of them written by women. Even the two men among the five young writers we reached out to are impressed by women writers writing in different languages. Also remarkable is the high number of translated works they recommend. Check how many of them you have read.

The Silence of the Hyena

By Syed Muhammad Ashraf

This is an unusual set of Urdu stories in a fresh translation by M. Asaduddin and Musharraf Ali Farooqi. It includes ‘The Beast’, a wonderful, allegorical novella that ought to be read widely in the Indian subcontinent. All the stories here describe power, abuse and betrayal through describing the world of animals, both in the wild and separate from human intervention, as well as the tricky ways in which the animal experience is embedded in our lives.

Chosen Spirits

By Samit Basu

This is a fast-paced novel with a multilayered political context. The author himself does not claim that it is especially dystopic, because much of what has been is a process underway. However, it is immensely readable and full of characters that you feel like you’ve met in real life, and at least some of them bring hope.

The Curse

By Salma

I had read and endorsed these Tamil stories, translated by N Kalyan Raman. Salma’s voice is unflinching and reflective as she tells stories about women, and Tamilspeaking Muslim women in particular. Few writers have described their inner lives and circumstances and the complex ways in which their identity is asserted, as Salma has done.

And Then One Day

By Nasiruddin Shah

I started it in English a couple of years ago and while I did enjoy it, I hadn’t had the time to continue then. This year, I discovered that it was also available in Hindi and Urdu, translated by the author himself, and so I ‘heard’ it read aloud. I had heard that the book was remarkable for both its honesty and the quality of its storytelling, and this turned out to be correct. People who are interested in film history, Indian theatre, or just stories about growing up in smaller cities in north India, will love it.

Dil ki Duniya

By Ismat Chughtai

This one is several decades old and I ‘heard’ it read aloud in the Urdu original (on the Katha Kathan YouTube channel) rather than having read it myself, but I would like to recommend it because it was one of the stories I’ve enjoyed the most in 2020. It is available in English translation as ‘The Heart Breaks Free’, one of four novelettes published as ‘A Chughtai Quartet’ and translated by Tahira Naqvi. This particular story is about the grief and constraints of being a sequestered and respectable woman in north India in the last century, yet it is told with such a deft, light touch, that you can’t help but laugh out loud every few pages.

Bread, Cement, Cactus: A Memoir

By Annie Zaidi

This has to be one of the most talked-about books in recent times and I have been recommending this to practically everyone I am talking books with. This is powerful writing. If Zaidi’s previous book, the novel Prelude to a Riot, was subtle in its expression of current affairs, Bread, Cement, Cactus is a no holds barred assertion of one’s identity and one’s place in this world.

Zaidi follows her life from her progressive upbringing in the industrial township of JK Puram in Rajasthan to searching for her roots in feudal Uttar Pradesh to her life and work in the metros. The part in this book that quite shook me up: the part about Zaidi’s grandmother being literate in Nastaliq and yet feeling alienated in public spaces – like, her bank – just because Nastaliq is not considered mainstream enough by the majority, because Nastaliq is a script for Urdu which is seen as a Muslim language!

It’s All In Your Head, M

By Manjiri Indurkar

Unabashed, outspoken, liberating—these are the three adjectives that kept on running inside my mind as I made progress with Indurkar’s debut book, a non-fiction account of her coming to terms with abuse and relationships that somehow showed – and in pretty negative ways – in the various physical/medical issues that her body faced. This book is like a catharsis. It takes courage to address issues that Indurkar has addressed, especially if one is writing about those issues, and especially if one is writing a first person, non-fiction account with actual people and places.

Victory Colony, 1950

By Bhaswati Ghosh

I am currently reading this book so I cannot write too many things about it. What I will still say is that I am loving what I am reading. Ghosh’s debut novel has the feel of a warm, snuggled-in blanket as several elements in the book – the delectable Bengali cuisine, the endearing daak naam with which Bengalis address their loved ones, etc. – are all familiar to me; but the world of this novel is not exactly a warm blanket but a smouldering furnace. The novel is set in the 1950s in Calcutta and deals with the plight of refugees from East Bengal. One cannot miss the empathy and eye for details that Ghosh has.

The women who forgot to invent Facebook…

By Nisha Susan

Nisha’s collection of stories came as relief in the midst of the pandemic, and I found myself turning in early every day, just so I could return to the page of the book.

The stories in the collection are deliciously wicked, twisted, hilarious and are comfortingly familiar, with a rather unfamiliar flow. Even as the stories progress, you really, truly have no idea where they’re headed. Nisha captures the thrill and the daring of women in the early Internet era especially, as well as a South India of many tongues, superbly in her stories.

The cock is the culprit

By Unni R and translated by Devika J

The book is a superb masterclass in political satire, that is about macho hyper nationalism, mob hysteria and the persecution of a manufactured enemy. A parallel for what the nation is undergoing today can quickly turn into an exercise in self-flagellation, a hopeless, deary read.

Unni R’s satire, translated to English from Malayalam by Devika, set around these horrid themes is, thankfully, imaginative and almost whimsical. It is comical even, when one sees up-close the seriousness with which those who want to cull ‘enemies’ take themselves. Set in a village, where a rooster is seemingly disturbing, with its ‘sarcastic crowing’, all events of national as well as religious significance, the story follows the frenzy of the villagers to capture and punish the offending bird.

Of oppressor’s body and mind

By Yogesh Maitreya

He is among the most interesting young writer-publishers of our times. His Panther’s Paw is an Ambedkarite publishing space that has been instrumental in bringing voices seldom heard in the English language to the fore. Yogesh’s most recent book, Of Oppressor’s Body And Mind, is a collection of his essays on language, literature and cinema. It does the rare job of inverting a gaze we are so very used to calling the norm. We study oppression and the oppressed but seldom do a critical study of the oppressor and his/her modus operandi, the ways in which they act and react, in our culture – books, cinema, etc. Yogesh’s essays are thoughtful, important readings for anyone looking to understand gaze. I’d certainly recommend it to storytellers who are trying to find a voice that is aligned towards justice.

Hellfire

By Leesa Gazi

This is an older book, a first novel by the British Bangladeshi filmmaker Leesa Gazi. The excellent translation from Bangla by Shabnam Nadiya hit the stands this year. And what a claustrophobic year to read about an adult woman in a seemingly normal family in Dhaka, who has never been allowed to leave the house by herself. It’s frightening to the point of terror because it goes from the too-familiar restrictions on women’s movement to batshit in a heartbeat and then shows you how batshit can also seem proper and traditional and totally acceptable.

The Majesties

By Tiffany Tsao

I read The Majesties soon after Hellfire and I was rocked on my heels and considered not reading or expanding my mind any further after it. Set in Djakarta, the story is of a young woman from a globe-trotting, worldconquering Chinese clan.

It begins with the massacre of every single guest at the patriarch’s birthday party by the protagonist’s sister. The protagonist, the sole survivor, is left in a coma but her brain is working at top speed trying to understand why her sister murdered everyone. The answer will make you lie down and stay with you for months. Double treat if you are into insects in general or butterflies in particular. Tsao is brilliant and courageous.

Headliners

By Lucy Parker

You can find romance novels for pretty much every taste and mood nowadays. The range is wonderful. For one of my favourite romance novels for the year it was a fight between Talia Hibbert’s Take a Hint, Dani Brown and Headliners. Hibbert has the sweetest male protagonists, very cool female protagonists and excellent banter.

Lucy Parker on the other hand has all of that and for me, the mysterious element of getting me ‘in the feels’. I usually dislike the ‘enemies to lovers’ trope but it works very well in the case of Sabrina Carlton and Nick Davenport, rival TV presenters who have been feuding publicly and are then forced to work together. I love Lucy. :)

Qabar

By KR Meera

At this point I am a biased partly about KR Meera, being a very public fangirl of this literary giant. Her new book, Qabar (in Malayalam) is a slim novel that begins in the courtroom of the protagonist, a young district judge with the hearing of a seemingly banal property dispute. But within minutes of catching sight of the plaintiff, Bhavana is thrown into a surreal world where nothing is what it seems, and the air is filled with flowers and snakes. There is a reason why over 8,000 copies have already been sold since the book came out in September 2020.

The King and the People

By Abhishek Kaicker

Kaicker’s book is the first to put the people of Delhi in the centre of history in medieval India. In so doing he sheds new light on Nadir Shah’s “Qatl-e-Aam” as the desperate tactic of a man who – barely opposed by the elite – found his troops slaughtered in the bylanes of the city by a public that would not submit.

With wit and learning Kaicker shows how class and caste operated in, and transformed in the rising prosperity of Shah Jahan’s Delhi, and how Aurangzeb’s use of religious community as one of the ways to rule led to the transformation of politics as people used it for their own purposes – from settling petty disputes to inciting revolution.

Why Men Rape

By Tara Kaushal

It is an undercover investigation in which she interviewed and profiled nine rapists across geographic, class and social categories. Combined with a depth of research, Kaushal’s book shines a light on a host of factors – confusion in law, the lack of understanding of the very definition of rape or consent, a sociopolitical reality based on exploitation and impunity, and a stunning lack of any real intimacy – that seems to hang around these people.

Under Red Skies

By Karoline Kan

It should be mandatory reading for those trying to get to grips with China. An absorbing, detailed memoir, Kan begins the story from before her birth as a second child while China’s One Child Policy was in place, with her mother’s will set against the state, of the price paid for the crime of wanting a daughter. Deeply informative, covering everything from Falun Gong to Tiananmen Square, this is a brave and forthright book from a journalist in China of how people live with Party rule.

Medieval Islamic Political Thought

By Patricia Crone

Published in 2005, the central question of much of the book is the search for a perfect leader, and the challenges of having imperfect ones. This deep desire is hardly unique to Islam, with strongmen proliferating around the world, from China to Brazil, and this deep dive in the complexity of politics in a world where an ideal ruler is always desired makes this history book surprisingly relevant.

Authors

Authors News Frontlist

Frontlist Article

Frontlist Book News

Indian Author News Frontlist

Indian authors

Writers News Frontlist

Writers We Read In 2020

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.