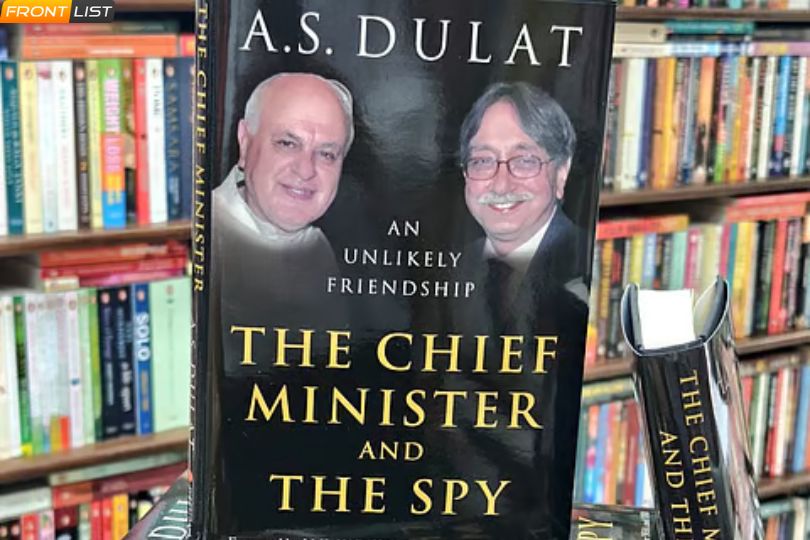

Dulat Memoir Sparks Controversy Over Article 370 Remarks

Amarjit Singh Dulat’s memoir ignites backlash over claims on Farooq Abdullah and Article 370, raising questions on media ethics and political impact.on Apr 21, 2025

Retired chief of the Union government's external intelligence wing, the Research and Analysis Wing, Amarjit Singh Dulat's latest book on Farooq Abdullah has caused a sensation in the print and electronic media.

The controversy – over Dulat's charge that Abdullah stated he would have assisted in the reading down of Article 370 if he had been brought into confidence by Prime Minister Modi – raises several issues regarding the morality of writing and publishing memoirs, and much more importantly, over how the Indian media downplays Kashmir, though unwittingly.

Starting with the latter, I have not as yet come across an article or an interview where Dulat has been asked directly if he had brought Abdullah's notice to his remark that Abdullah "would have assisted" had he and his party been put in the know about the reading down of Article 370.

Yes, Dulat submitted his manuscript to Abdullah. However, he didn't call to Abdullah's attention the critical paragraph independently, by a message or a phone call.

In interviews, he has tried to play down the statement as one of 'heartbreak', issued in the backdrop of a security clampdown and large-scale arrests. Is he suggesting that Abdullah did not mean what he is accused of having said? And why include it all, then?

Both Dulat and his interviewers are aware that the charge carries huge implications for Abdullah and his party, the National Conference, as well as for Kashmiri politics and rights.

No Kashmiri leader has ever endorsed reading down Article 370, though some in the past have enabled its erosion. Those erosions were not unremarked. There was widespread Kashmiri resentment at the bit-by-bit seizure of the state's rights to decide its administration and economy, which encouraged dissidents, enabled Pakistan increased entry into the valley's politics and Pir Panjal, and finally and perhaps least, contributed to the electoral downfall of those leaders who had permitted erosion.

By the time the Modi government took power, Article 370 was symbolic rather than practiced, but as we all know, the more remote a symbol is from its soil, the more powerful it gets.

The Modi government well knew that; it knew that it could withdraw autonomy only by taking draconian action and so it did, seriously injuring Indian democracy mortally.

Kashmiri resentment at the reading down of Article 370 is almost universal. Even in Ladakh and to a lesser extent Jammu, where the move was hailed, most are now regretting their earlier embrace of it.

Against this background, to accuse one of Kashmir's main politicians, president of its then-ruling party, of going as far as to compromise over the issue would not only de-legitimize the leader, the party, and the government elected in Jammu and Kashmir, but indicate that Kashmiris approve of the new status quo.

As all Kashmir observers like Dulat are aware, that is not the case. But none of Dulat's interviewers lingered over the adverse effect of his accusation on Kashmiri politics and the questions of Article 370, statehood and civil rights, or asked him if he had anticipated it when he penned the book.

Two of the top analysts – Karan Thapar and Vir Sanghvi – did examine the charge and what it entails, but also switched to speak of Dulat's other remarks on the personal relations of the Abdullahs.

Thapar inquired whether he did not believe the book would ill-fit the Abdullahs; Sanghvi noted that the charge was being abused to provide a reason for reading down Article 370, but permitted Dulat's defense of the "we would have helped" remark and the suggestion of opportunism that went with it to pass. In fact, he went even further: Abdullah did not repudiate that phrase in his response to the press, he stated (from what Abdullah has stated it does not appear that the phrase was mentioned to him; he repudiated the charge in its entirety).

Others may claim that I am exaggerating one paragraph. But I am not writing about the entire book, merely the paragraph which made the headlines. Those who accept Dulat's memory as true will exploit the paragraph; those who may doubt, particularly in Kashmir, will still be reassured in the opinion that their politicians have no principle.

Indians and especially Kashmiris have always been cynical towards politics and politicians. What happened in 2019 and its aftermath consolidated Kashmiri cynicism to an extent of complete distrust of any assertion of constitutional and rule-based politics.

A glimmer of hope emerged with the elections of September-October 2024, which re-energised Kashmiri politics. After eight long years, Kashmiris had an elected administration, even if it was severely restricted by the Union home ministry.

A dose of disappointment has set in in the six months since then, at the failure to achieve movement on statehood and several snubs by the home minister and the lieutenant governor. And here is this book, with another bitter pill for the cynics to swallow.

So, does a memoirist need to keep the potential effect of his book in mind as he writes it? That is clearly a matter of personal choice. For the journalist, however, it is not a matter of personal choice. S/he must include context as well as effect, and in this instance, combining a far-reaching political accusation with Dulat's insights into the Abdullahs' interpersonal relationships cheapens the former.

In the good old days of the Northern Ireland peace process, the majority of top British journalists, including within the BBC, balanced a story in terms of its effect; if the story was not important in itself and could potentially harm peace talks, they spiked it.

Dulat's accusation, in the light of his description of it, was evidently trivial. Its effect, however, was strongly adverse to the extent that it was playing into the hands of those who legitimize the use of force to take away autonomy and ignore Kashmiri outrage at the act. To believe that the problem will just blow away is a mistake – the cynicism it has injected will only make it stronger.

While so, the argument has made the lame duck government even lamer. It will even end up pushing statehood further back; as per Dulat, there is no way the Modi government will restore statehood anytime in the near future. These points merit a separate show, exclusively on the impact on Jammu and Kashmir, including on chances of peacemaking.

A second question is whether a publisher should publish a memoir without verifying whether individuals quoted in it have given their approval to the quotations. Since Dulat's book is a memoir, the question enters a grey area. But I would like to know if his editors even asked themselves the question or what the adverse effect of a part of the book could be, however minor.

Ethical publishing is not fashionable in our nation, but Juggernaut is an independent publisher with some credentials of integrity. I wish they too will reflect on the fallout this book has caused and how to mend it. By his interviews, Dulat seems to be attempting to mend the fallout; can the reprint, which I have no doubt will soon occur, cut out this paragraph?

Memoirs tend to avoid fact-checking because they are an individual's recollection. However, when they have damning political accusations, reviewers, interviewers and commentators fact-check for themselves to put matters straight. And if a memoir belittles vital issues of people's and states' rights, even by insinuation or accident, it should be subject to rigorous fact-checking.

Maybe that will occur when the reviews are published. The situation in Jammu and Kashmir is bad enough not to need any further agitating.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.