Angria: A Historical Odyssey

Dive into 'Angria,' a richly detailed historical novel, exploring the life of Kanhoji Angre amidst political intrigue and naval conflictson Feb 26, 2024

.jpg)

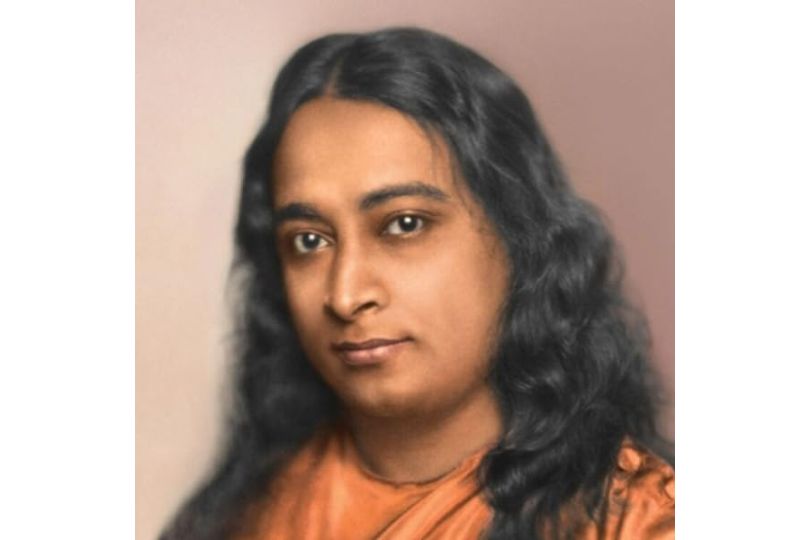

Sohail Rekhy was born in Mumbai to actors Waheeda Rehman and Kamaljeet and spent several summers and countless weekends on the shores of Raigad District. He grew up in Bangalore, fascinated by Indian history, and went on to study literature at the University of Toronto. Sporadic journalism and freelance copywriting always kept him by his pen, as he worked in advertising and television industries and dabbled in sustainable furniture. This is his first novel, a fruit of years of research and writing. He currently lives with his wife and daughter in Bhuta.

Frontlist: What inspired your exploration of the historical narrative of Kanhoji Angre, and how did your personal connection to the shores of Raigad District influence your writing of "Angria"?

Sohail: I was researching piracy on the western coast of India when I first came across the legend of Kanhoji Angre. It was a colonial description of him as a pirate. Further research astounded me on two levels: first, despite being a diligent student of South Asian history, I had not heard of Kanhoji Angre and second, an accepted narrative that had painted him a privateer for over 300 years had persisted. Both shocked me. The fact that my granduncle was a Commodore stationed at INS Angre and I had grown up looking at Kandheri and Undheri islands, off the coast from the site of many summer holidays, made me wonder about my ignorance of him. Outside of Maharashtra, Kanhoji Angre remains an unknown figure. I wanted to address these issues, and having grown up in those environs, I found the flora-fauna, geography, and gastronomy well established in my imagination.

Frontlist: Given your background in advertising and television, how did these experiences shape your ability to craft cinematic imagery in "Angria"? How do you believe your professional background contributed to the visual storytelling elements within the novel?

Sohail: Of course, all past experiences and training come to bear, and given that my primary mandate was to popularize the legend of Kanhoji Angre, I did initially think of writing a screenplay, as films are much more popular than books these days. But the scope of a novel, with both the depth and width it can provide in the mind's eye, is incomparable. It's the difference between a photograph and a painting. But I also feel that if you are aware of the production, it grounds you, and you are, at some level, thinking about how this can be translated to film. But one should take care not to let it limit your storytelling. I try to present perspectives for the action and always show rather than tell, which is a more engaging way of storytelling and what I work towards anyway.

Frontlist: How did you navigate the challenge of developing Kanhoji Angre's character within the constraints of historical context and the gaps in available information? Were there specific instances where you incorporated fictional elements or took creative liberties to enhance the narrative while staying true to the essence of the historical figure?

Sohail: Fortunately, we have several sources from the period and the history of the times is well established. But as far as Kanhoji Angre went, especially in the earlier years, there was very little information. What is available in Marathi bhakars is hagiographic and does not inform us of his motivations. What I relied on was the tenor of his language in letters he had written to the Company or to the Portuguese. I built around that ghost I could feel from his words: his attitude and his character. It is known that Kanhoji studied with Pandit Joshi at Harnai, where Balaji Bhat, the first Peshwa, also studied -- the depth of their friendship is my own assumption, but his sense of loyalty was not an embellishment. History must not contradict the liberties one takes. A lot of things fell into place, and I took them to be serendipitous. I had the bones and the clothes he wore and had to flesh out everything in between.

Frontlist: In the process of delving into the lesser-known aspects of Kanhoji Angre's life, and while vividly portraying naval conflicts in "Angria," were there specific challenges you faced? How did you navigate these challenges to strike a delicate balance between maintaining historical accuracy and crafting an engaging narrative of sea battles?

Sohail: The period just after him, that of the Peshwa's, is very rich in sources, and one can extrapolate the priorities and cosmology of people of the period. Battles, in fact, have many more extant sources than personalities do. Battles were well described, and there are several sources for both battles of the period and of Kanhoji's innovations. Archaeological proof in the form of cannons, shots, fortresses, and dockyards is available, too, and provides an accurate picture of the times. We also have several Company and Portuguese sources on naval battles and the weaponry and methods that were used. The sons of Kanhoji used these methods, which are well documented in the years that followed. Kanhoji's love for horses was typical of his class, as was his tendency to acquire the latest muskets and fine swords.

Frontlist: The dialogue in "Angria" authentically captures the historical period while remaining accessible to modern readers. Can you elaborate on your approach to crafting dialogue that strikes this balance, ensuring both historical accuracy and resonance with contemporary audiences?

Sohail: I was careful to avoid words and concepts that were not contemporary to the period on the one hand and avoided imposing any sense of the archaic on the speech. The dialogue of the English characters was easier to recreate as we have source material exemplifying 18th-century speech. But for dialogue spoken by the Konkani characters, I used straightforward and simple speech as I find in Marathi a directness that is unadorned yet lyrical. I have assumed that we continue to speak as we did in the past and were flowery in speech only when circumstances dictated. However, when one needs to indicate Persian or courtly influence, one needs to allude to Persian's ornate nature. Different languages have different tendencies, and the tendency of English was to acquire words for the new things they were encountering. In one instance, I quoted a letter from Kanhoji verbatim, and those words are the bedrock of his character, his language, and the soul of the novel. I have tried to stay true to that essence.

Frontlist: In "Angria," were there particular cultural nuances or regional details you intended to emphasize in the narrative, and what strategies did you employ to ensure that readers could fully grasp these references and vividly visualize the characters in the historical setting?

Sohail: I did not want to ignore the cultural realities of the time, especially when it came to caste or class strictures, precisely because they provided such well-defined jumping boards into the reality of the times. How and what people ate or whom they could eat with became a tool to explore the culture and the region. The inherent wealth of the region and its primacy as an entrepot was crucial to the story, and that was explored at every opportunity by creating characters of the banking and trading castes and their relationship with the aristocracy.

Frontlist: In "Angria," the narrative delves into intricate political complexities involving conspiracy, war, and family politics. Could you elaborate on how you navigated through these layers to weave a cohesive storyline, and were there specific challenges you faced in portraying the political landscape of the time?

Sohail: I am still awaiting judgment on whether I have been able to do that, as it was a very exciting and complex period. The Mughals were warring amongst themselves, the House of Bhonsle was divided, regional satraps were making power plays for themselves, and the Europeans were trying to establish trading monopolies. I had to immerse myself not only in Maratha history, both the era of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and the subsequent Peshwa period, but also in researching the Portuguese, the early years of the English and Dutch Companies, their interactions, and the complexities of the Siddi Mahals. Though this is a very well-documented period, it is more cantankerous and confusing from a historiographic perspective. The challenge was always to keep it simple and not lose focus on the main characters. In the end, a lot of editing and rewriting was done, but having spent almost six years at that point, the material had become a part of me. Then, it was a question of being a guide to the reader and, drawing their attention to certain aspects and ignoring others so as not to confuse them. In this, I must give credit to my agent, Kanishka Gupta and historian and writer Amish Raj Mulmi, who helped me thresh out the chaff.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.