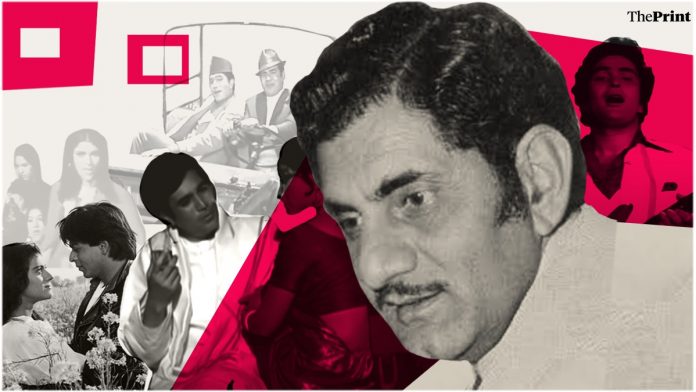

Anand Bakshi almost gave up on Bollywood. Then came Bhagwan, Bhala Admi, a ticket collector

Anand Bakshi almost gave up on Bollywood. Then came Bhagwan, Bhala Admi, a ticket collectoron Apr 23, 2021

Back in the 1950s, when he first arrived in Bombay, it had been difficult for him to make a breakthrough. Writers, composers and film-makers worked in set teams; they had their own favourites and did not want to ‘experiment’ with newcomers. Film-making is expensive and film-makers, in my own experience too, are very superstitious. They pursue hits often blindly and shun people associated with flops as blindly. In the ’50s and ’60s, music composers and lyricists were a very close-knit group, and a newcomer could not easily get the attention of the composers. Bakhshi made it a point to meet three or four people daily to ask for work. He would also visit film studios— like the Famous Studios in Mahalaxmi, Kardar Studios in Dadar and Filmistaan in Goregaon among others—every day. A few composers did not take him seriously as a writer when they felt that he wanted to be a singer too and that may have worked against him.

His family lived in Lucknow, I was told. And he lived here on his own as he could not afford to bring them to Bombay. After a few months in Bombay, when he could not find work as a truck driver or car driver, he even pretended to be a motor mechanic and landed a job. But the owner of the car garage soon found out that Bakhshi was not good at the job on the very first day. and told him to leave. These minor misfortunes aside, Bakhshi was soon to land a film, his first, which he considered his biggest film ever! Far bigger than Sholay and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge decades later.‘Meri sabse badi film’

Desperate for a break and scared he would run out of his savings, Bakhshi would visit all the film and song recording studios in Bombay, waiting for long hours to meet any film-maker or composer he could run into. The ex-fauji strategized it all like a war drill, aiming to meet at least five people daily before returning to his room. During one such strategized visit, he was waiting outside the office of actor Bhagwan Dada (Bhagwan Abhaji Palav) at Ranjit Studios. Bhagwan Dada was a star actor in those days, working on his directorial venture Bhala Admi, produced by Brij Mohan. Bakhshi befriended the ‘office boy’ and found out that Bhagwan Dada was stressed about his lyricist not having turned up for a song sitting that day and was looking for a replacement. Bakhshi seized the moment and ‘encountered’ Bhagwan Dada—by barging straight into his cabin to ask for work! Bhagwan Dada was taken by surprise and asked him what he wanted. Bakhshi said he was a songwriter looking for work. Bhagwan Dada said, ‘Let’s see if you can write a song.’ He then narrated the story of the film to Bakhshi and gave him fifteen days to write the song. Within fifteen days, Bakhshi had managed to write the lyrics of four songs. It was not a difficult task for him, because in his army days he would rewrite all the songs, in his own words, of some of the films he’d enjoyed watching. Bhagwan Dada liked all the four songs and signed him as the second lyricist of the film. It was an action film, something Nand had loved watching in his formative years. He was paid Rs 150 for these four songs. The first one—‘Dharti ke lal, na kar itna malal, dharti tere liye, tu dharti ke liye’—was recorded on 9 November 1956. The music composer was Nisar Bazmi who a few years later migrated to Pakistan. Within two months of his second stint in Bombay, the geetkar had been finally born. ‘I thought I’d conquered the world! I thought all my problems were over. Little did I realize that they’d only just begun!’ The film took two years to complete, was a box-office failure and went unnoticed. So did Bakhshi. For the next six years, he did not have much work in the movie industry. A decade later, a few months after the success of Jab Jab Phool Khile in 1965, Bhagwan Dada happened to meet the geetkar Anand Bakshi at a film party. He was going through a low phase in his career as an actor and advised him, ‘Anand Bakshi Sahib, khushi ki baat hai, aap ka bahot naam ho gaya hai. Magar ek baat yaad rakhna, ke yahan iss duniya mein aadmi ko naam se zyada us ka kaam zinda rakhta hai (It’s great to know that you’ve made a name for yourself. But always remember that what a man needs to survive in this world is good work rather than just a name).’ As Dad told us, ‘I never ever forgot those golden words from my first benefactor in the industry.’ Bhala Admi was released in 1958, two years after the songs had been recorded. Bakhshi had still not found work in films. He was writing a song or two every few months; for some of these he received payment but his name was not credited. ‘When I saw my name in the credits, I cried in happiness. Today, if I am called a successful writer, it is because of Bhagwan Dada.Bhala aadmi

Bhagwan Dada was the first bhala aadmi (kind soul) who gave Anand Bakhshi his break in films in 1956. Bakhshi had walked into his office and asked for a chance to write. Nearly two years later—the film Bhala Admi had not yet released—Bakhshi had a chance encounter with another bhala aadmi, at the Marine Lines railway station—a place he would sometimes visit to write poems. Dejected, disappointed, disillusioned a second time from life in Bombay, he had never faced such rejection and humiliation as a fauji among civilians, a hopeless Bakhshi was quite aimlessly sitting at the Marine Lines station, writing down his thoughts and contemplating his immediate return home, a defeated soldier-poet. He was approached by a Western Railway ticket checker, who asked him to show him a valid travel ticket. Bakhshi had none. He was asked to pay a fine for loitering. Bakhshi had no money for the penalty. The ticket checker noticed that Bakhshi had written some Urdu verses in his notebook and questioned him about it. Coincidentally, the ticket checker was a lover of poetry and on finding out that this ticketless man was writing poems, he asked him to narrate what he had written and even sat down beside him to hear more closely. He was impressed by Bakhshi’s writing and asked him to recite some more. He liked all that he heard. He asked the poet, ‘What are you doing here?’ Bakhshi felt at ease telling him all about his family’s journey as refugees from Pindi to Delhi and about his second attempt to make it in Bombay as a film artist. The ticket collector, strangely, treated him to tea and samosa. By the time they finished their snack, the ticket collector, straight out of the blue, offered, ‘Bakhshi, you write well. You must not go back. Stay here in Bombay. I am certain you will get a break. Your writing is as good as the film writers who are big names today.’ On learning Bakhshi had no money to stay back in the city—his father and father-in-law having refused to support him any longer— the ticket checker suggested, ‘I live alone in Borivali. My family lives in Agra. It gets lonely, and I would like the company of a poet. You stay with me, and I don’t want any rent from you. You narrate your poems to me. When you get work, you can look for your own accommodation.’ That very day, in May 1958, the ticket collector Chhitar Mal Swaroop took Bakhshi, a stranger, to his house at 24H, Jawala Estate, S.V. Road, Borivali West, Bombay. He kept this stranger at his home for the next three to four years! Never charged him a rupee and never asked him for any favour all his life. He would even give him pocket money of Rs 2 daily, to eat and travel, to see producers and directors and ask them for work. He would sometimes slip a rupee or two into Bakhshi’s empty wallet, so that the latter would not feel humiliated asking for money. Bakhshi said, ‘I never asked nor found out why he helped me without charging me or asking me to ever pay him back when I got established.He was a farishta (an angel) that my Bansi Wale sent to help me during the worst period of my life.’ Chhitar Mal Uncle would visit us nearly thrice a year. He always brought Agra ka petha for Dad and us. I never heard my dad address anyone in his life as ‘Ustaad’ except Chhitar Mal uncle. He addressed Dad as ‘Bakshiji’. So, I believe, Anand Bakhshi had two mothers, one who gave him birth, Sumitra Bali, and the second, Ustaad Chhitar Mal. ‘Had Chhitar Mal not stopped me from returning to Delhi or to the army, I, a married man, with a two-year-old baby, would have gone back home and would not have had the means, the will or the courage to make a third attempt.’ This bhala aadmi was responsible for every single film opportunity that arrived on Anand Bakhshi’s path until he passed away in 2002. Chhitar Mal Uncle passed away in 2001.

Source: https://theprint.in/

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.